The tariff powers case now before the Supreme Court may be one of the more important cases in American history. I’ve been participating in the tariff powers case from the start as an amicus curiae, a friend of the court, as a lawyer, historian, and former official who has some experience with emergencies.

Confronting any great public choice, the beginning of wisdom is to understand the history of the issue. The modern evolution of tariff and emergency powers is a history obscure even to most lawyers. In the litigation so far, both the judges and the lawyers have picked out pieces of the relevant history and most are only beginning to comprehend it. The reference works don’t make it easy. Yet understanding this history illuminates this momentous case like a noonday sun.

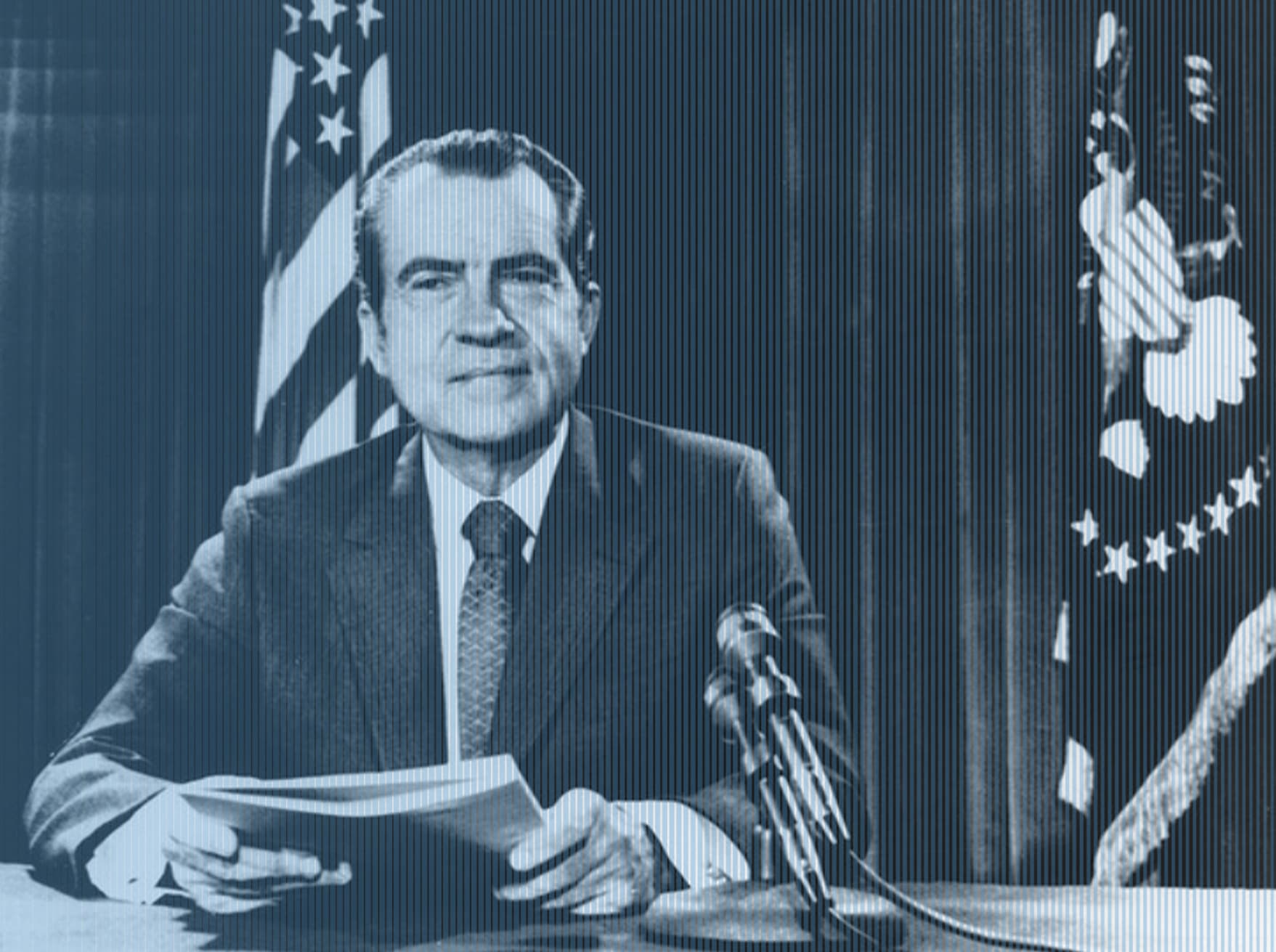

The Constitution assigns the tariff-setting power to Congress. In 1971 President Nixon declared a national emergency and imposed a temporary surcharge on imports. In 1975 a lower appellate court upheld this, citing an emergency powers law. The same emergency powers language was later re-enacted in 1977 in the International Economic Emergency Powers Act (IEEPA—pronounced eye-ee-pah).

The administration’s defense of President Trump’s emergency tariff powers relies entirely on this precedent.

The 1971 story is the linchpin of its whole position. According to the administration, the 1977 law ratified President Nixon’s use of this emergency power. Now President Trump has taken it to town.

The real history lights up a different story. President Nixon had not claimed emergency powers when he imposed his surcharge. The trade lawyer who drafted his executive order in 1971 recalls the episode clearly. He regards the current administration’s legal position as “totally unfounded in America’s trade laws.”

The real story reveals how carefully both the Congress and the White House managed and reconciled their powers back then. Reacting to the 1971 crisis, in 1974 Congress reined in presidential power. It settled how to handle crises like that one. It then greatly elaborated its power to set and implement tariffs. The history reveals the full enormity of what President Trump’s unconstitutional decrees have done to a system Congress painstakingly built over a period of more than a hundred years.

The differences between friends and enemies

Tariffs are part of trade law. Trade law and sanctions law arise from two old and very different legal traditions.

Tariffs tax Americans who engage in normal trade relations with friendly countries. Article I of the Constitution expressly gives Congress two sets of powers over such relations. It gives Congress the specific power to determine tariffs. It separately gives Congress the power to regulate commerce with foreign nations.

Up through the First World War, the United States had a general tariff system set by the Congress. This was supplemented by trade treaties with some individual countries—usually called treaties of commerce and navigation. These individual deals might set special tariff rates only for goods from that country. Such treaties were ratified by the Senate, preserving final congressional approval. Douglas Irwin has written a fine standard history of trade policy.

By contrast, the tradition of sanctions law is part of an opposite legal tradition, governing non-commerce with enemy countries. It primarily targeted foreigners, not Americans. The tradition grew out of long practice in handling specific problems of trade and property relations in wartime. The wartime context could bring in some presidential powers as commander in chief, and therefore for national defense, in Article II of the Constitution. Aditya Bamzai has written a good law review article summarizing the evolution of this tradition. When the United States entered the First World War in 1917, Congress codified this tradition in the Trading with the Enemy Act (TWEA—twee-ah). The TWEA included a power to “regulate . . . importation” of foreign property

From 1917 on, neither Congress nor the White House confused such warlike practice with the parallel and elaborate world of normal trade law and tariff authorities. Congress enacted law after law governing tariffs and trade agreements—notably in 1922, 1930, 1934, and 1962—and no one thought that all this was unnecessary because the TWEA supplied some alternative way of doing tariffs.

During the Cold War, as the United States began wielding emergency powers under TWEA without a formal war, courts understood that these measures were still just targeting foreigners in enemy countries. For example, a landmark test of these powers came before the Second Circuit in 1966. The case involved a Cuban named Juan Sardino who was trying to get his money out of the United States and bring it to his home in Cuba. Writing for the court, the renowned jurist Henry Friendly explained:

“We are not formally at war with Cuba but only in a technical sense are we at peace. . . . The founders could not have meant to tie one of the nation’s hands behind its back by requiring it to treat as a friend a country which has launched a campaign of subversion throughout the Western Hemisphere. . . . Hard currency is a weapon in the struggle between the free and communist worlds; it would be a strange reading of the Constitution to regard it as demanding depletion of dollar resources for the benefit of a government seeking to create a base for activities inimical to our national welfare.”

The court then treated the case as analogous to a wartime seizure of assets.

Action against foreign adversaries was exactly the issue when the Supreme Court visited the IEEPA language (similar to the old TWEA language) in the Dames & Moore case in 1981. IEEPA was used to freeze Iranian assets after American diplomats were taken hostage in 1979. The case arose when the United States negotiated the Algiers Accords to get the hostages back in exchange for putting the assets into a prolonged arbitral process. The plaintiffs had their own complaints against Iran and wanted a piece of the assets. The court protected the government’s right to do its deal, while also stressing the case should not be used as a precedent.

“MFN” and “normal trade relations”

As the First World War ended, American leaders thought they needed to update the way they did trade deals with friendly countries. Some still wanted general tariffs. But the patchwork of customized individual trade deals created discrimination. Importers of French wine might have to pay one rate; importers of Spanish wine might pay another. The victim of such discrimination, France or Spain, might retaliate by discriminating against importers of American goods.

The solution to such problems was to adopt the practice of granting “most favored nation” status. A preferential tariff given to one country was extended unconditionally to all countries with whom one had a trade treaty. As countries concluded trade treaties, they extended this “most favored nation” status to their partners.

In 1919 the Republicans were a pro-tariff party. The Democrats were against. Leaders in both parties agreed, however, that the incoherent patchwork of tariff rates and country-by-country trade agreements had become unworkable for the advanced America of 1919.

Influenced by a landmark report of the bipartisan US Tariff Commission, Democratic and Republican leaders, pro- and anti-tariff, chose a new approach. Douglas Irwin calls this 1919 report “one of the most influential government documents on trade since Alexander Hamilton’s Report on Manufactures.” The commission argued that the United States should pursue an approach of equality of treatment toward the goods of other nations, whatever the general tariff rate:

“It can not be too much emphasized that any policy adopted by the United States should have for its object, on the one hand, the prevention of discrimination and the securing of equality of treatment for American commerce and for American citizens, and, on the other hand, the frank offer of the same equality of treatment to all countries that reciprocate in the same spirit and to the same effect. The United States should ask no special favors and should grant no special favors. It should exercise its powers and should impose its penalties, not for the purpose of securing discrimination in its favor, but to prevent discrimination to its disadvantage.”

Once they regained the presidency and Congress in 1921, Republicans adopted the new approach in their tariff bills. They did this in two steps.

First, in 1922 the Fordney-McCumber tariff law adopted a general tariff schedule and section 317 of that act delegated to the president authority to penalize, with tariffs up to 50 percent, any country which refused equal treatment and discriminated against the United States. The same provision was re-enacted again, in section 338 of the next big tariff bill, the Smoot-Hawley Act of 1930.

Second, in 1923 President Harding and congressional leaders, notably Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, who chaired the committee that would review any new trade deals, agreed that in the future the United States would negotiate or renegotiate its individual trade treaties with unconditional equal treatment in agreed rates. America would adopt the “most favored nation” principle and practice. One can read the instruction that Secretary of State (later Chief Justice) Charles Evans Hughes sent to his diplomats (Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States 1923, vol. 1, 131-32 (1938)).

All subsequent presidents, until this one, then followed this practice in their trade negotiations. The Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act of 1934 (RTAA) granted broad authority, regularly renewed, for presidents to negotiate new trade deals and enact the results with presidential proclamations. The RTAA practice had become too unwieldy by the beginning of the 1960s. It was then replaced by the Trade Expansion Act (TEA) of 1962.

The high tide of presidential tariff-setting power—broad advance negotiating authority and tariffs enacted by presidential proclamation—ran from 1934 to 1974. As such agreements proliferated, the tariff schedule had two columns. One listed the “general” rates for countries with MFN. Column 2 listed the “statutory” rates under Smoot-Hawley that applied to others.

After 1974, Congress took back the authority to implement revised tariff rates with legislation that also addressed nontariff barriers. Every trade deal after 1974 continued, as before, to rest on express negotiating authority granted to the president by Congress. Any general trade deals after 1974 had to be enacted by congressional legislation to approve the package deals involving tariffs and nontariff barriers.

Congress repeatedly codified schedules with unconditional equal treatment. In 1998 Congress decided to call this MFN status with the more accurate label: “normal trade relations.” By 2025 the United States had such “normal trade relations” with all but four countries in the world.

This is the body of laws that President Trump has overthrown in 2025. He has undone the “normal trade relations” approach to trade deals that the United States has used, and prospered from, for more than a hundred years.

Since the Constitution firmly gives the authority over these decisions to Congress, and since there is law after law codifying its tariff decisions since 1974, the puzzle then is this: how could the president even think he had authority to undo them all?

1971 and all that

The answer to this question is a comic opera of misunderstanding. It is a strange and twisty story revealed only by deploying the historian’s microscope.

The backdrop was a genuine crisis, a monetary crisis, in 1971. The context was the collapse of the Bretton Woods system that had linked the value of the dollar to gold. The American current account surpluses that had been usual since the 1930s had turned to a deficit, for reasons both domestic and foreign. The concern, growing through the 1960s, came to a head in August 1971. Jeffrey Garten has a nice recent account of this story.

In the secret “three days at Camp David” that Garten writes about, the Treasury Department worked with the president to make the surprise announcement that the Bretton Woods system was finis; the United States would no longer convert its dollars into gold. Worried about a too-sudden depreciation of the now floating US dollar, the executive order included a “temporary” surcharge of 10 percent on imports covered by Column 1 of the tariff schedule.

The 29-year-old Treasury lawyer who drafted this order was Alan Wolff. Wolff would go on to greater things but, discussing the episode with me, he still remembers this momentous time quite well.

Wolff and his colleagues were perfectly clear on where to get the authority for this surcharge. Under the 1962 law, as with its 1934 predecessor, the negotiated tariffs in column 1 of the schedule were implemented by presidential proclamation. Both the 1934 law (amending the 1930 Smoot-Hawley law) and section 244(b) of the 1962 law gave the president authority to “at any time terminate, in whole or in part,” any of these rate proclamations. So, the lawyers thought, they would just use this termination power to justify the temporary surcharge. The head of the Justice Department’s Office of the Legal Counsel, William Rehnquist (later chief justice), approved. The executive order expressly cited this authority.

Wolff’s immediate boss, Michael Bradfield, told him to call the situation a national emergency. But the proclamation was still based on explicit congressional delegations in those 1934 and 1962 trade laws. No one suggested that the TWEA be cited as authority for the surcharge.

The surcharge was lifted four months later, in December 1971. By 1973, both the Nixon administration and the Congress decided to reset the whole framework for authorizing and implementing trade deals. Wolff, now working for the office of the Special Trade Representative (the predecessor to the current USTR), worked on that bill too, which became the Trade Act of 1974.

In 1973 and 1974 the White House and Congress carefully hammered out the new balance. The congressional barons like Russell Long (D-Louisiana), the chair of Senate Finance, firmly exerted their influence. After it was over, Wolff wrote an article detailing the “evolution of the executive-legislative relationship.” Like a geological record, Wolff wrote, “the enactment of a major piece of legislation, in an area such as trade negotiations, which involves major Constitutional powers of the Executive and Legislative Branches, records the relationship between the President and Congress. . . .” His article is an invaluable snapshot now, precisely because it shows just how these matters were viewed in 1975 from the point of view of the executive branch’s principal trade lawyer.

The result, Wolff observed, was “a much more active Congressional role in the execution of trade policy.” Presidents lost their broad authority to negotiate trade deals and tariffs. In the future presidents had to seek “fast-track authority” from the Congress to conduct a negotiation that would involve both tariffs and nontariff barriers, with guidelines specified in the legislation. Presidents would no longer in practice implement the deals through proclamations.

The package deals had to be presented to Congress and enacted by joint resolution that could pass both houses. From that time to the present, Congress has never changed this fundamental reallocation of authority.

To deal with a crisis like 1971, the administration could therefore no longer look to the “proclamation/termination” authority it had relied on back then. As Wolff worked on the new bill, drafted in 1973 and passed by the House in December 1973, he and his colleagues saw that it included a new section, section 122, that granted authority to do about what the administration had done in 1971—an emergency surcharge of up to 15 percent, strictly time-limited to no more than 150 days.

Meanwhile, litigation was winding its way in court challenging the legality of the 1971 surcharge and seeking refunds. In that case the government lawyers ran into an argument that the “termination” authority could not be used for a mere temporary suspension or to articulate some new rate, i.e., a 10 percent increase. The government lawyers were not trying to maintain the surcharge, which was long gone. To win the claims case, they then added another justification, invoking the TWEA as well.

In July 1974 the U.S. Customs Court (predecessor to the current Court of International Trade) rejected both arguments. It held that the surcharge had been illegal.

This rejection did not matter much to Congress or the White House. The surcharge had ended two and a half years earlier. The Trade Act of 1974 was fixing any question about authorities. That act passed the Senate at the end of 1974 and was signed into law by President Ford in January 1975.

Meanwhile, not wanting to repay all the claimants from 1971, the government had appealed the Customs Court decision. In November 1975 the old Court of Customs and Patent Appeals (now the Federal Circuit) ruled in the government’s favor. It agreed that the proclamation/termination authority that the Nixon administration had originally used was not sufficient.

But, that court concluded, the claims could be refused and the surcharge could be retrospectively justified under the TWEA’s authority to “regulate . . . importation.” No one had ever before thought this was a power to set tariffs.

The court then did all it could to limit this odd, anomalous holding. It explained that the surcharge was so limited in scale and time and limited only to areas that had been the subject of prior tariff concessions (handled by presidential proclamation), that it could let this stand. Its unease obvious, the court warned that this did not mean it would “approve in advance any future surcharge of a different nature, or any surcharge differently applied, or any surcharge not reasonably related to the emergency at declared.”

This case was, the appellate court explained, “quite different” from the supposed worry of a president who could come along “ ‘imposing whatever tariff rates he deems desirable.’ ”

As if that were not enough, the court added: “The declaration of a national emergency is not a talisman enabling the President to rewrite the tariff schedules.” And the court further added: “The Executive does not here seek, nor would it receive, judicial approval of a wholesale delegation of legislative power.”

In this crabbed fashion, the court retroactively granted authority to a president, authority that—at the time—President Nixon had neither invoked nor sought!

Happily, the real struggle over trade and tariff power had taken little notice of any of this. It had been settled by the beginning of 1975. Congress had quite firmly intervened, as I’ve explained above. Not only had it reset the authority for what had been done in 1971, it had reclaimed its power on both ends—initiation and approval of any trade deals.

Given what even the executive branch thought had happened by 1975 in delineating the relevant trade and tariff-setting powers, it was natural that, when the TWEA language was re-enacted by Congress in 1977 as the IEEPA, no one on either end of Pennsylvania Avenue seemed to think this was significant, certainly not for trade policy. Indeed, when President Carter signed the IEEPA into law, he said, “The bill is largely procedural. It places additional constraints on use of the President’s emergency economic powers in future national emergencies. . . . ”

To reiterate: since the country’s founding, America has had one body of law to handle taxes or tariffs on Americans engaged in normal trade relations with friendly countries. There has been quite another body of law to handle commercial relations, or non-relations, with enemies.

There was this one anomaly. It turns out to be the strange case of a novel litigation strategy adopted in 1974 to keep from repaying years-old claims from a 1971 surcharge that the president had actually justified on trade law grounds.

Other than that, these two distinct bodies of law—for friends and for enemies—have coexisted equably until 2025. Over more than a hundred years, neither Congress nor the White House thought a president could freely substitute one body of law for the other.

“Whatever tariff rates he deems desirable”

The Supreme Court is not bound by prior rulings of inferior courts. As it looks back on the twisty story of the early 1970s, a striking point is that in 1971 neither President Nixon nor his lawyers had wished to arrogate novel emergency powers. They had acted under trade law, to temporarily terminate presidential trade proclamations. There was no thought of superseding any congressional enactment.

The other striking point is that, as a result, Congress so greatly strengthened its control over the whole process of trade deals and tariff setting in the new setup after 1974. It is not credible to assert that, in 1977, Congress—re-enacting TWEA language in IEEPA—thought it was delegating some sweeping power to throw out all of its legislative enactments.

Under the system created in 1974, huge efforts were later expended to sometimes seek “fast-track authority” to make trade deals. No one in those intense debates argued that they were really all wasting their time because (didn’t they know?) presidents already had plenary tariff-setting emergency power in IEEPA.

Congress had covered all the bases. If countries weren’t trading fairly with us, there were provisions for anti-dumping and countervailing duties (sections 1671-1677n of the 1930 law as amended), provisions for discriminatory barriers targeting American products (section 338 of the 1930 Act), or provisions for unfair trade practices (section 301 of the 1974 act, as amended). All US tariffs, whatever their authority, were non-discriminatory, unless the country was unfairly trading with us in one of the specified ways. National security claims about dangers to sectors of American manufacturing or agriculture are covered in section 232 of the 1962 act.

The Tokyo Round of the GATT (1973–79) went through this new process of legislative approval. The results, including tariff adjustments, were formally enacted by Congress in the Trade Agreements Act of 1979 before President Carter could implement the new tariff rates.

The Trade and Tariff Act of 1984 added authority for bilateral deals that would eliminate tariffs altogether while working on nontariff barriers, and set up a fast-track process to approve such joint deals. The first use of this was for US-Israel, and Congress implemented it in the US-Israel Free Trade Area Implementation Act of 1985. The next move, much bigger, was with Canada, which Congress implemented in the US-Canada FTA Implementation act of 1988.

There were thirteen major agreements of this kind. All were implemented with legislation passed by Congress, with Jordan (2001), Chile (2003), Singapore (2003), Australia (2004), Morocco (2004), Dominican Republic-Central America (2005), Bahrain (2006), Oman (2006), and Peru (2007). Successors were Colombia (2011), Panama (2011), Korea (2011), and Mexico (2020).

The Omnibus Trade Act of 1988 granted authority for the Uruguay Round of the GATT. Section 1103 of that act again confirmed that the president had to submit the entire package—tariff rates and nontariff deals—to Congress for approval. The Uruguay Round Agreements Act of 1994 was the implementing legislation for the adjusted tariff rates as well as the rest. Only then could President Clinton do an administrative proclamation.

I review this detail to give some sense of the number of acts of Congress that President Trump has overridden with his executive orders.

President Trump has no authority to negotiate any general trade deals at all. Congress granted the last such authority in 2015, and the authority expired in July 2021. It has not been renewed. And the 2015 bill expressly prohibited any president from raising tariffs by proclamation.

More than that, claiming IEEPA authority from the supposed 1971 precedent that I have unpacked above, President Trump has undone more than a hundred years of US trade policy based on unconditional equal treatment of countries with whom we have normal trade relations, all of it ratified by Congress.

On this thin claim of emergency powers, he has returned the United States to the patchwork that prevailed before the First World War—the patchwork that seemed unworkable in 1919.

But President Trump has done so with a singular difference. Before 1919, the problem was the difficulty in making trade agreements because all the presidents obeyed the Constitution. Congress set tariff rates and ratified trade treaties. Now, the chaos is compounded by the disregard of any meaningful governing authority, constitutional or statutory.

This approach would have appalled past pro-tariff Republicans. Tethered only to one man’s whims, this approach to tariffs and taxes will probably also be found to violate the Constitution. Thus, compounding the chaos, the US government is likely to be required to refund to Americans, with interest, the tens of billions of dollars already collected under the unlawful use of emergency powers—a liability that grows by hundreds of millions of dollars every day that system stays in place.

The supreme irony is that all this is being justified by an invocation of presidential emergency powers rooted in a 1971 precedent. Yet in that very episode the president and his lawyers had not invoked such powers.

Philip Zelikow is the Botha-Chan Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution. For twenty-five years he held a chaired professorship in history at the University of Virginia, where he also directed the nation’s leading research center on the American presidency. Zelikow focuses on critical episodes in world history and the challenges of policy design and statecraft.