Shortly after President Trump’s second inauguration, I published an article exploring whether a “Trump Doctrine” might emerge in his second term that would entail two things: the reassertion of US dominance in the Western Hemisphere, and a US retreat from the Eastern Hemisphere and its nettlesome flashpoints like Ukraine, the Middle East, and Taiwan.

The first part certainly appears to be coming true.

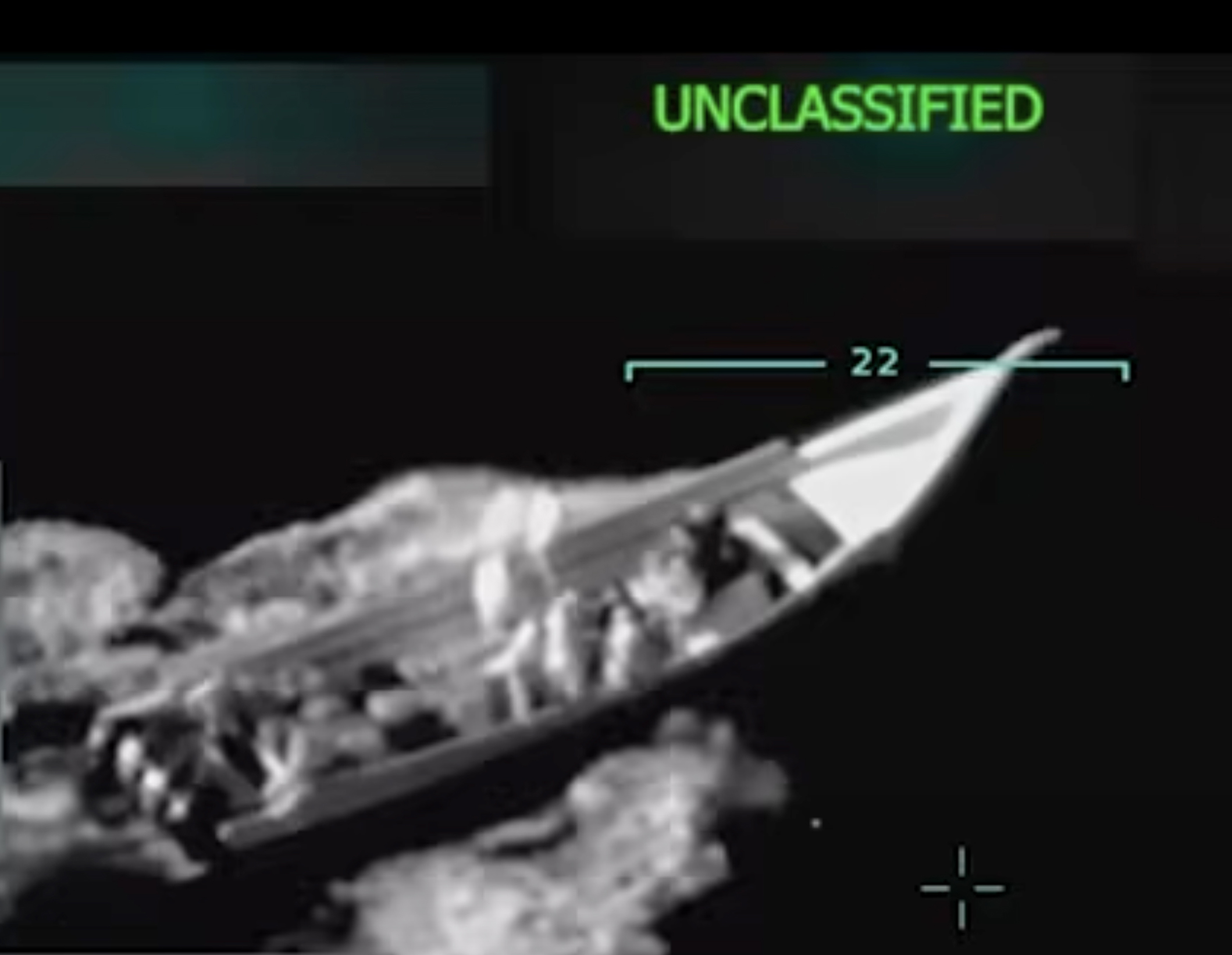

Minutes into his inaugural address last January, Trump was already throwing his weight around in the Americas. His regional policies so far include military strikes on alleged drug runners in the Caribbean; gunboat diplomacy aimed at Nicolás Maduro’s dictatorship in Venezuela; an (as-yet-unresolved) attempt to push China out of the Panama Canal; punitive tariffs on Brazil, Mexico, and Canada; and (mostly unwelcome) entreaties to Canadians and Greenlanders to transfer their national sovereignty to Washington. Clearly, the 200-year-old Monroe Doctrine (a policy justification for US regional hegemony) has been resurrected by Trump in his first year back in office.

But the second part—US retreat from the Eastern Hemisphere—so far hasn’t come to pass. Indeed, Trump has bucked the isolationist wing of the Republican Party (and key members of his administration) to bomb terrorists in Yemen, crater Iranian nuclear facilities, strengthen NATO, and keep the pipeline of American arms flowing to the front in Ukraine. These are sound policies that have kept wars from metastasizing and strengthened US security.

How then to reconcile Trump’s actions with the reportedly isolationist thrust of the Pentagon’s draft national defense strategy? In short, some of the president’s staff want a different foreign policy from their boss’s.

This is especially true in the Pentagon, where most of the newly appointed civilians are unknown to the president. Many come from isolationist traditions and organizations at odds with Trump’s foreign policy successes in his first and second terms.

Trump, like his Pentagon civilian staff, relishes homeland defense and a strong hemispheric posture. But unlike some of those staff, Trump doesn’t believe it should come at the expense of America’s status as a global superpower.

Yet the Pentagon’s draft national security strategy would reportedly do exactly that: weaken America as a superpower. According to the Washington Post, senior-level uniformed officers (whose instincts seem closer to the president’s) have “raised serious concerns” about the draft strategy for “narrowing” America’s ability “to deter and, if necessary, defeat China in a conflict.” They also objected to the strategy’s reported goal of weakening US power in Europe and the Middle East, the Post reported.

No question, Trump believes US allies must rapidly strengthen their own defenses rather than rely solely on US protection. But unlike some of his subordinates, Trump understands that deterrence also requires American military strength and presence far from America’s shores. Nowhere, including in his remarks last week to hundreds of US flag officers, has Trump called for a weaker, less capable, and less global US military. In his second term, the president has repeatedly called upon a strong military to bolster diplomacy, deter adversaries, and apply force.

In the Middle East in March, Trump launched military strikes on Houthi rebels in Yemen who had been attacking American commercial and military vessels. In June, he bombed Iran’s nuclear program, preventing a far worse crisis down the line if Tehran were to acquire such weapons. Trump is demanding that Hamas release hostages and pressing Israel to wind down the war in Gaza—a prelude, he hopes, to expanding his first term’s Abraham Accords by brokering diplomatic ties between Israel and Saudi Arabia.

Trump’s diplomatic overtures carry special weight thanks precisely to the backdrop of global American military power.

In Europe, Trump may have stunned US allies with his “reciprocal” tariffs, but he has also helped to strengthen the NATO security alliance. At the NATO summit in the Netherlands in June, member states assented to Trump’s demand that they increase defense and security expenditures from the current level of 2 percent of GDP to 5 percent by 2035. They did this not as a personal favor but because peace depends on the US president and the military might he commands. Trump reasserted an “ironclad commitment” to Article 5, which holds that an attack on one NATO member is an attack on all.

“I left here differently,” he said at the end of the NATO summit. “I left here saying that these people really love their countries. It’s not a rip-off, and we’re here to help them protect their country.”

Trump is confounding the “isolationist” label elsewhere, too. Far from abandoning Ukraine, he is sustaining the flow of US weapons to the front lines (so long as Europe pays for them). In a White House meeting with allied leaders in August, he pledged logistical support for a European peacekeeping force in Ukraine to safeguard any future peace settlement—a pointed dismissal of Russian dictator Vladimir Putin’s bellicose objections to any Western military presence in Ukraine.

Trump is now moving to increase economic pressure on Russia and its key backers to incentivize a peace settlement. He is pressing Europe to impose sanctions and tariffs on Russia and China for their involvement in the Ukraine War—and has offered to mirror any steps Europe takes. Last week, during the United Nations General Assembly in New York, Trump suggested Russia might be a “paper tiger” and said Ukraine should get “all their land back.”

In Asia, Trump’s policy direction is murkier. His idiosyncratic diplomacy in South Asia and his imposition of punitive tariffs on India managed to alienate Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi—the same leader with whom Trump, in his first term, successfully cultivated a strategic partnership.

On China, Trump has made unilateral concessions to Beijing, weakening US restrictions on the export of powerful AI chips and settling for continued Chinese control of TikTok’s algorithm, which determines what news and videos are seen by more than a third of all Americans. Trump’s pursuit of a trade deal with China—despite Beijing having ignored the terms of its 2020 trade deal with Trump—and his administration’s chilly treatment of Taiwan have unsettled US allies in the Western Pacific.

Even so, odds are good that Trump will see Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s ambitions much as he has come to see Putin’s: as something destabilizing and ultimately threatening to the national and economic security of the United States. Trump’s acerbic social media post commenting on Xi’s September summit with the leaders of Russia, North Korea, and Iran is a good indication that Trump’s suspicions are growing.

The president has sometimes underestimated how helpful—or harmful—midlevel staff, including at the Pentagon, can be to his foreign policy agenda.

Pentagon staff undermined the president (twice) last summer by reversing his decision to let Europe purchase US weapons to support Ukraine. (A trusted National Security Council staff can be his eyes and ears for detecting such insubordination, but only if he invests in rebuilding the NSC.)

As President Trump heads toward the second year of his second term, he will be glad to have a military befitting the world’s top superpower—and not the timid military posture reportedly described by the Pentagon’s national defense strategy, which appears to be at odds with his motto of “peace through strength.”

Matt Pottinger is a distinguished visiting fellow at the Hoover Institution. He served as President Trump’s deputy national security adviser from 2019 to 2021. He also is the editor of The Boiling Moat: Urgent Steps to Defend Taiwan and fought in Iraq and Afghanistan as a US Marine.