The past twenty-five years have taught us that economic crises can hit suddenly, sending the economy into deep recession. In response to the 2008 financial crisis and the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, the US government spent nearly $7 trillion on stimulus packages to prop up the economy. Before the next crisis hits, it’s prudent to assess the costs and benefits of stimulus spending.

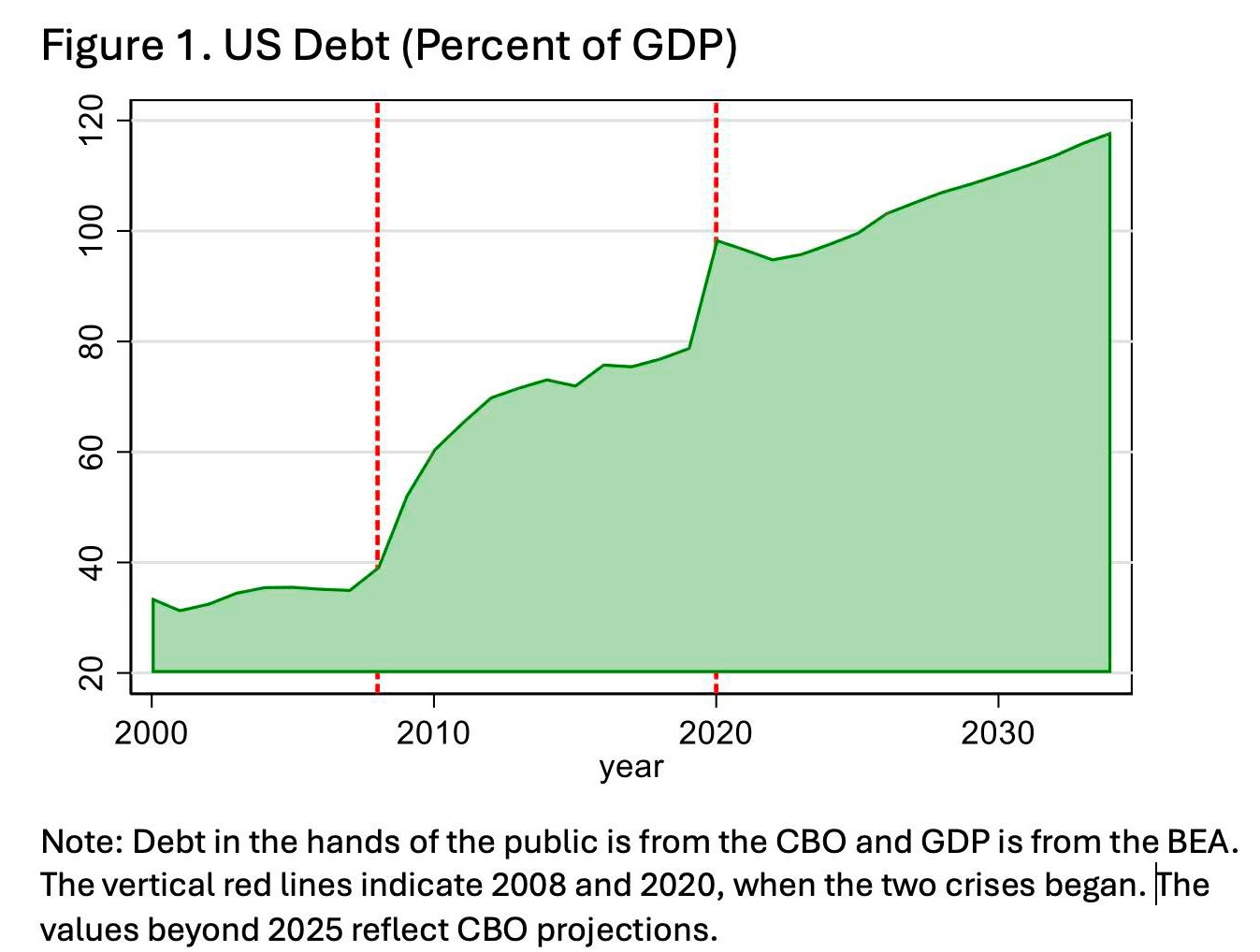

Consider first the costs. Figure 1 shows the ratio of government debt to GDP, which now stands at 100 percent. The deficits created by the stimulus packages account for 27 percent of that debt. During each crisis, the debt level ratcheted up to ever-higher levels because Congress made no effort to pay down the debt after the crisis had passed.

The debt level is so high that the United States now spends more on interest payments than on defense. The problem will only get worse, since the aging of the population is projected to raise spending on Social Security and Medicare. By most accounts, the United States is now on an unsustainable debt path.

How much bang did we get for our seven trillion bucks? During the crises, many policymakers and academics thought that each dollar of government spending would raise GDP by $1.50 or more. They believed in Keynesian economics, which argues that the government can lift an economy out of recession merely by spending.

For these policies to work, consumers must spend a significant fraction of their extra income on goods and services, and businesses must respond to the extra demand by hiring more workers rather than raising prices. These two conditions allow the government spending to multiply through the economy and raise GDP.

We can judge the effectiveness of the policies by estimating how much they raised aggregate consumption, GDP, and/or employment. Some earlier research estimated relatively large effects. However, some of the latest research has re-examined the data and reached the conclusion that the policies were not effective in stimulating the macroeconomy, at least in the short run. Here are details for some of the biggest components of the stimulus packages.

Temporary transfers to households

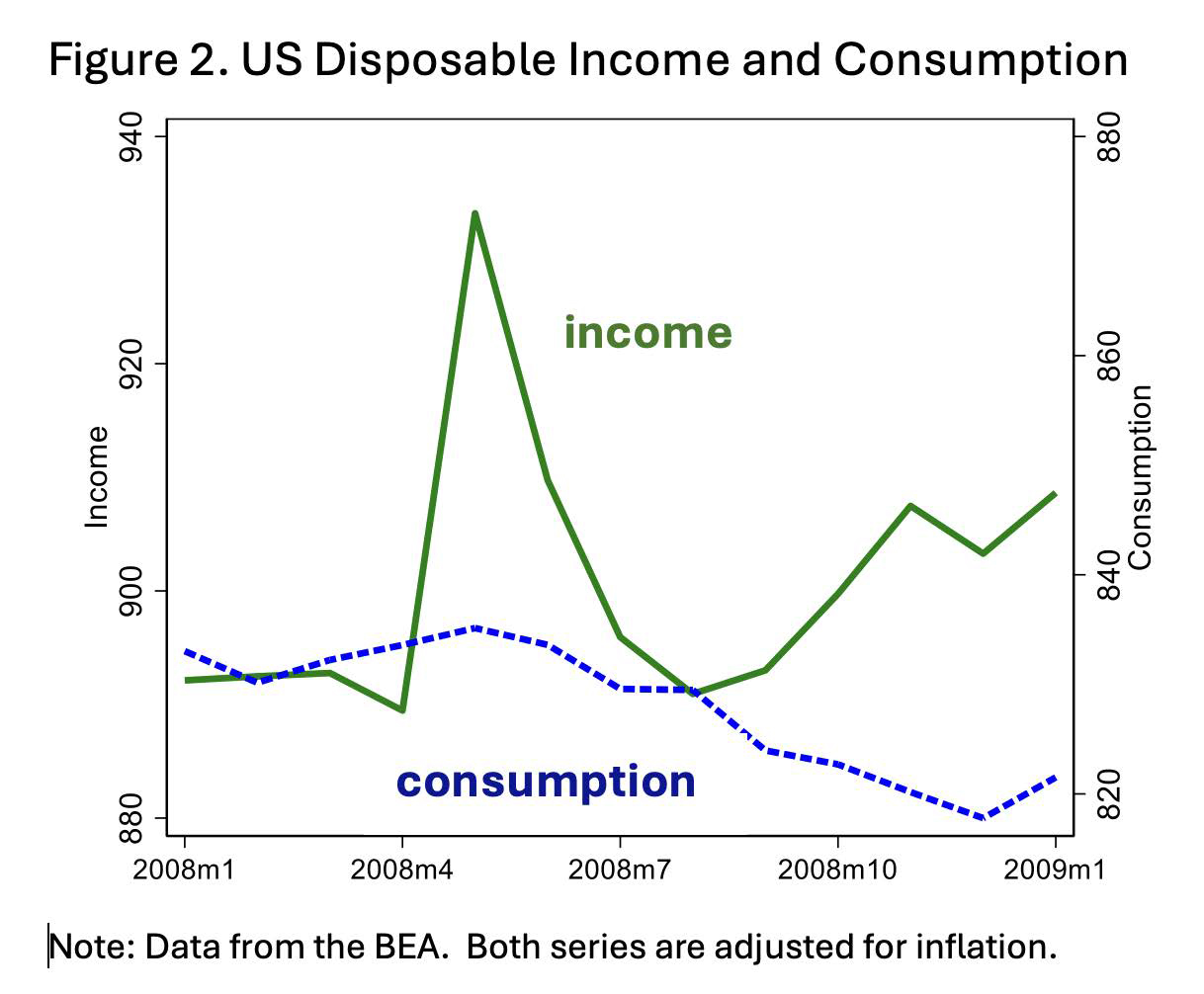

During both crises, the government sent checks (transfers) to households to stimulate consumer spending. For example, during the financial crisis the government distributed tax rebates averaging $1,000 to most households in late spring and summer of 2008. Some influential early studies used household-level datasets and estimated that the average household spent between 50 and 90 cents of each dollar received within the first three to six months. That should have provided a big boost to aggregate consumer spending.

However, there is no evidence of such a boost in the aggregate data. In a recently published paper, my coauthors Johannes Wieland and Jacob Orchard and I pointed out that income spiked up with the arrival of the rebates, but consumer spending rose only slightly (figure 2). If households had spent as much as the estimates suggested, there should have been a big spike in consumption, even after accounting for the fall in consumption from the collapse in housing prices.

To figure out why aggregate consumption didn’t increase much, my coauthors and I went back to the household data and re-estimated the spending responses using new and improved statistical methods. Our new estimates implied that households mostly saved the rebates; the only spending we detected was on autos. Our new findings of low household spending responses are consistent with other recent work, including a 2020 meta-analysis of 144 studies by Tomas Havranek and Anna Sokolova. We concluded that the 2008 rebates did not help lessen the recession.

During COVID, the government distributed more than $800 billion in stimulus checks to households in three rounds from March 2020 to March 2021. Household-level studies by Parker et al. in 2022 and Baker et al. in 2023 estimated that households raised their consumption spending in the first few months by around 25 cents per dollar of stimulus. The Parker et al. study calculated the implied effect on aggregate consumption and found that it was small.

Thus, the transfers during COVID likely had only a modest stimulus effect on consumption and GDP during the crisis.

Ongoing research is exploring the extent to which the stimulus payments led to the high inflation in 2021 and 2022. Recall that Keynesian stimulus works only if businesses increase production rather than prices in response to higher demand. If businesses can’t raise production, they instead raise prices, and the stimulus ends up as inflation rather than higher output.

Aid to state and local governments

Both the Obama stimulus passed in 2009 and the COVID packages granted aid to state and local governments. For the 2009 stimulus, the research implies that it cost somewhere between $50,000 and $112,000 per job-year created (Chodorow-Reich 2019, Ramey 2019). The implied cost was much more during COVID. Clemens et al.’s 2025 study estimates a cost of $603,000 per job-year created. Auxiliary evidence suggests that state and local governments mostly saved the federal aid they received during the pandemic. Thus, while there may have been some stimulus to jobs during the financial crisis, there was very little during COVID.

Paycheck Protection Program

The Paycheck Protection Program distributed more than $500 billion in guaranteed and forgivable loans to small- and medium-sized businesses over a four-month period after the initial COVID lockdowns. The goal was to prevent job loss. Several studies have estimated that the job effects were relatively small, given the size of the program. For example, a study by Granja et al. 2022 estimated effects that imply a cost of $175,000 per job-year saved. The study found that the funds weren’t always allocated to the neediest businesses and that many businesses mostly saved the funds.

Government infrastructure

Spending on infrastructure is a popular component of stimulus packages, since it promises to help the economy in both the short run and the long run. While the evidence suggests that infrastructure brings benefits in the long run, it doesn’t work well as a short-run stimulus.

As my 2021 study demonstrated, the long time lags between the passage of legislation and the actual spending on infrastructure projects make this type of spending an ineffective short-run economic stimulus. Despite the Obama administration’s efforts to find “shovel ready” projects, the authorized funds were spent slowly over time.

Andrew Garin’s 2019 study of the effects of the 2009 infrastructure stimulus on local areas found that a dollar of government spending led to an increase in construction payrolls of 30 cents. However, the study found no evidence of Keynesian spillovers into the rest of the local economy.

No illusions

The US government spent almost $7 trillion on its stimulus packages during the financial crisis and COVID. The interest cost on the stimulus-related debt is now almost $300 billion per year.

The latest research shows that most of the spending didn’t produce much “bang for the buck” in the form of macroeconomic stimulus. In most cases, households, state and local governments, and businesses saved most of their transfers from the federal government, so they didn’t generate additional spending and hiring when it was needed.

If a future crisis hits, policymakers should not fool themselves into thinking that government spending can provide more than a modest stimulus to the macroeconomy. They should instead keep in mind the cost in terms of unsustainable debt paths.

Valerie A. Ramey is the Thomas Sowell Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution and a research associate of the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). She co-leads Hoover’s Economic Policy Working Group and participates in Hoover’s Long-Run Prosperity Working Group. She is also a professor emeritus at the University of California–San Diego, where she taught for thirty-six years.