For decades, the United States lived in a world where its dominance was assured, economically, militarily, culturally. Despite the rise of China, until recently Beijing rendered no real challenge to American power. During the Cold War, the United States inhabited a bipolar world, carved into rival spheres of influence. And while this time was not without its anxieties over the Soviet challenge, by and large US power, autonomy, and agency were assured. The United States generally did what it wanted, when it wanted, without significant constraints. These ventures were not always successful—witness the Vietnam War—but the nation’s ability to act, rather than react, was assured.

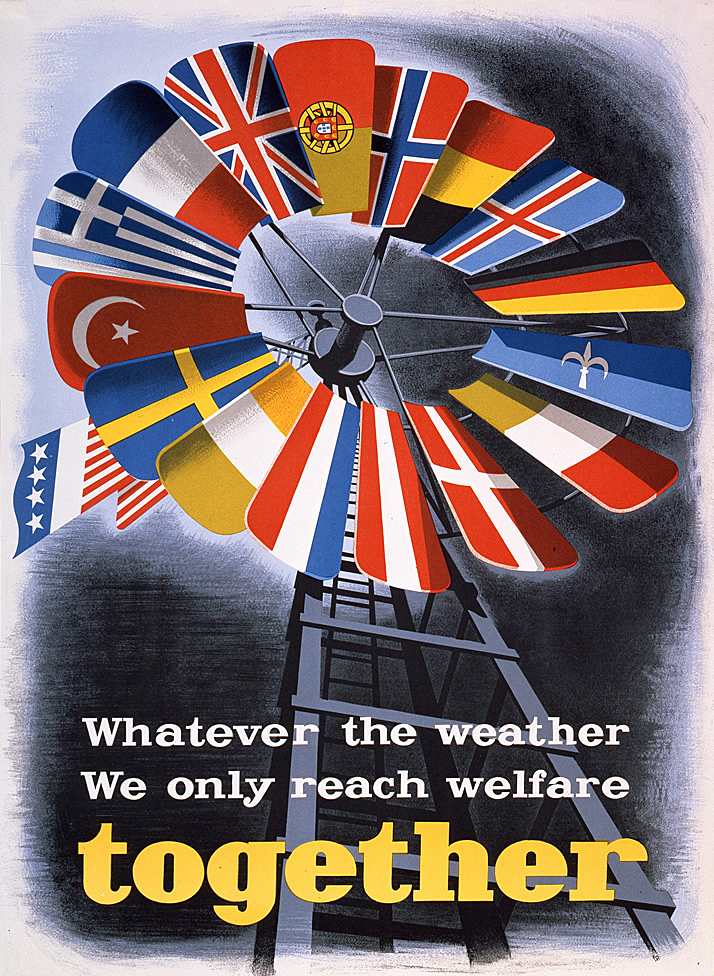

Paradoxically, this dominance meant that the United States often acted multilaterally—in concert and in consultation with its vast web of allies and tribunes. Indeed, the United States had created this vast web in the postwar era, conjuring up an empire to rival Britain’s, but one held together not by armed conquest but by bureaucratese: NATO, the UN, the WTO.

These were the unrealized dreams of Woodrow Wilson that crashed so spectacularly in the early years of the twentieth century. In the era after World War II, these dreams were made reality by FDR’s underestimated successor, Harry Truman, and the string of both Republican and Democratic presidents who followed.

Global trade and the rise of the dollar system are a case in point. In the aftermath of World War II, the United States underwrote a global trading system that on its face valued the reconstruction of postwar Europe above all else. But this reconstruction, although it depended at first on American largesse, grew robust through economic relations that benefited both the United States and its allies.

Access to American markets was critical to restoring the healthy functioning of European society and withstanding the communist menace. It was also critical to integrating Japan into global society. Witness the rueful joke of the 1980s: forty years after the war, Germany and Japan had finally won.

Follow the money

Related to trade came the rise of the dollar. Akin to a United Nations for finance, the Bretton Woods agreements, signed in New Hampshire in 1944, provided a system for international currencies to trade against one another at predetermined rates. Like the United Nations, Bretton Woods was supposed to prevent future conflict, and it birthed other multilateral organizations like the World Bank and the IMF. But its most important result was unforeseen and accidental: placing the US dollar at the center of global trade.

Although signatories could technically exchange their currencies for any other currency party to the agreement, it turned out that everyone wanted dollars. Mostly, this meant the United States could borrow at lower rates, since demand for dollars was high. But as time went on, increasingly dollar supremacy meant that the United States sat at the crossroads of global trade, with its financial tentacles reaching into nearly every corner of the developed and developing world. Reinforced by American financial institutions, practices, and regulations, the dollar weathered the rise of globalization, the collapse of the Soviet Union, and the entrance of China into the world economy.

Across the late twentieth century, an unspoken consensus emerged: the United States, the most powerful nation in the global system, veiled and bound its power.

To be sure, under the rubric of fighting communism, the nation’s military might landed harshly on small nations drawn to socialism and any political movement that might lead to communism. And there were cracks in the façade: most notably the Iraq war, which started with the pantomime of multilateralism but quickly shifted to unilateralism when the United Nations proved too slow. But in this global system, power hid its face and so grew stronger.

What’s being lost

What we see now, writ large across the Trump administration, is a new level of impatience with multilateralism—and not coincidentally, what is emerging in the global system are the first signs of a multipolar global system. Again, trade proves the most illustrative example.

Whatever their latest iteration, the Trump administration’s aggressive tariffs signal a definitive break in how the United States engages the world. The Trump administration has rightly perceived the economic web that hems it in—like the fabled Gulliver, the United States is a hegemon tied down by a thousand small Lilliputians. What President Trump seems not to grasp is why this web was created, and how it operates to maintain American power. Or perhaps the administration has grasped this web and is making a clear trade-off. Certain of Trump’s advisers seem to believe that a multipolar world has already arrived—or will be inevitable—and hence the United States must change its ways.

One backdrop of the administration’s economic policy is a conviction that we stand at the threshold of Bretton Woods 3: a new world where global trade will flow through multiple financial channels. Core to US dominance has been the invoicing of oil in dollars, a tradition that grew out of the 1970s oil shocks. But the recent willingness of oil producers to accept payment in other currencies threatens this arrangement and was likely a motivating factor in recent US tariffs on India, which has reportedly settled most of its Russian oil trades in rubles.

Theodore Roosevelt famously advised the United States to speak softly and carry a big stick. The Trump administration instead speaks loudly, but its critics worry the stick it carries is woefully small—that we have already lost critical technological ground to China, that we are being played by Vladimir Putin, that we are decimating our intellectual capital and losing our sense of national unity amid ever-sharpening partisan animosity.

Even the certainty of US military supremacy is no longer a sure thing, amid fiscal overextension and a decline in military preparedness.

At this point, we can’t know all the trade-offs involved in the shift away from multilateralism. One thing is clear: in the last global contest for hearts and minds, the United States triumphed because of its culture and values. It was Coca-Cola and Hollywood that were known and imitated worldwide, understood as the taste of freedom, the vision of liberty and the pursuit of happiness open to all.

Russia and China locked their people in—and it was America where they longed to be.

It may be possible to act unilaterally without compromising America’s dominance, reputation, and alliances. But mostly, America’s leaders now act as if there is no trade-off: that it is possible to act unilaterally and maintain the same level of American power and autonomy that was established through multilateral statecraft and a globally admired culture. If the administration isn’t clear on what is at stake, the rest of us ought to be.

Jennifer Burns is is a research fellow at the Hoover Institution and an associate professor of history at Stanford University. She is the author of two acclaimed biographies based on research in the Hoover collections: Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Right, and Milton Friedman: The Last Conservative, which was named a best book of 2023 by The Economist and a finalist for the Hayek Prize. At the Hoover Institution, she is part of the History Lab and directs an annual summer Workshop on Political Economy.