In 1931, somewhere near Dallas, a seismic recording truck rattled down dusty roads.

The truck belonged to a small outfit called Geophysical Service Inc. (GSI). Eugene McDermott and colleagues were trying to find oil. All over, from Louisiana swamps to Saudi deserts, GSI workers set off explosions and listened for echoes from below, suggesting where to drill.

No one could have predicted what was coming. Within a generation GSI’s scrappy surveyors had become Texas Instruments, the company that invented the silicon transistor, the integrated circuit, and more. What began as an oil-discovery business later forged the most essential underpinnings of modern digital life.

The lesson to be revealed? Transformative technologies do not appear fully formed. They often emerge from improbable beginnings and desperate disruptions. But only if people are reorganized in ways that recognize reality, allow and support innovation, and drive institutional change.

Invention and reinvention

On December 6, 1941, the four GSI principals bought out the company, becoming sole owners. The next day, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. GSI’s global oil discovery crews had to be called back. “Oil discovery as a service” was no longer a viable business model.

Instead of finding oil beneath the earth, perhaps GSI could detect German submarines beneath the waves? A contract from the War Department helped save the company. GSI started making magnetic anomaly detectors to hunt U-boats in the Atlantic.

GSI’s transformation didn’t stop there. Within a decade, GSI had become General Instruments and then, after a name conflict with another defense contractor, Texas Instruments.

War and crisis forced adaptation. The ability to realize non-trivial institutional and business changes was as essential as technical know-how.

Imagine that

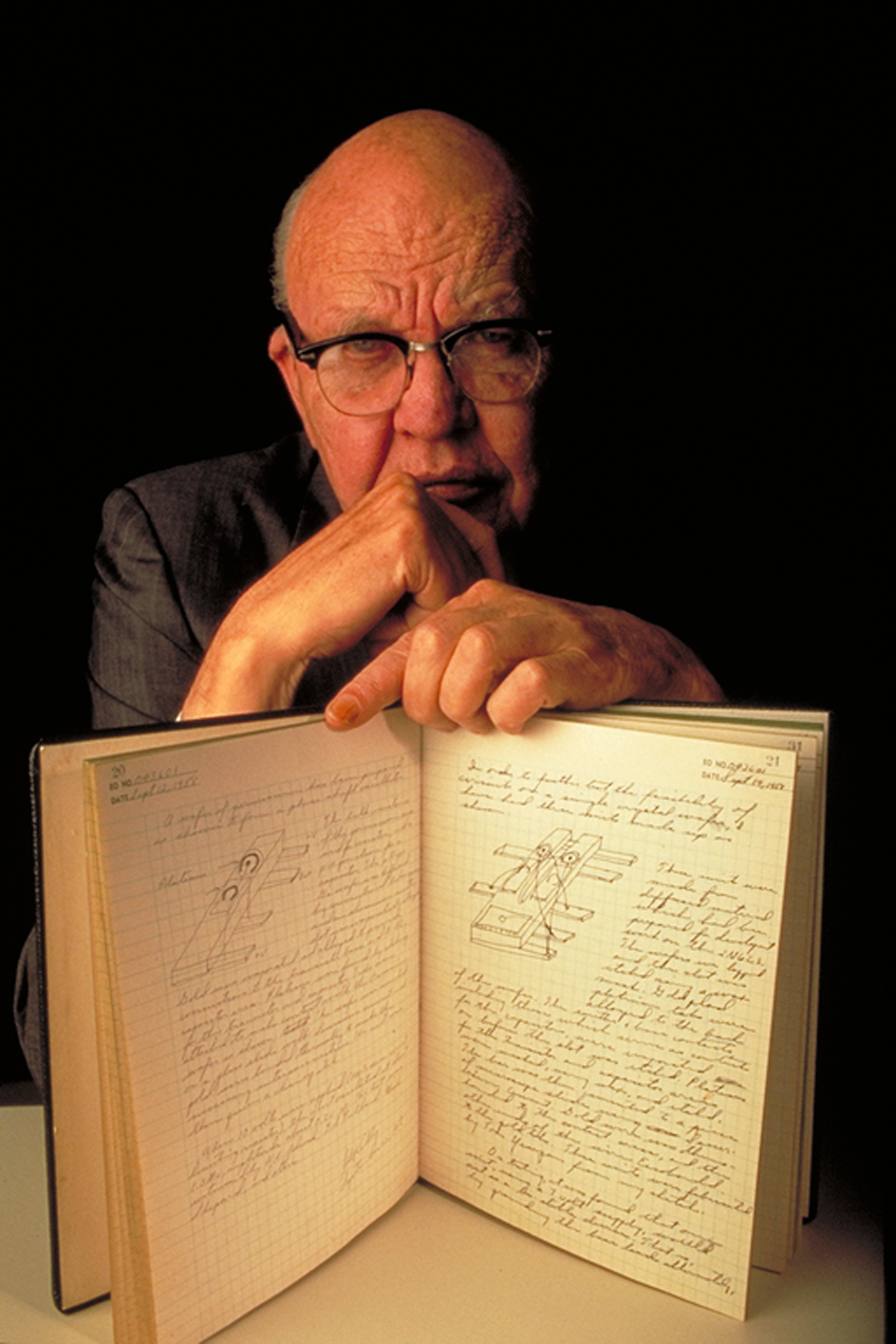

Jack Kilby had been working in Wisconsin for a decade, designing components for consumer electronics at the Centralab Division of Globe Union. He became excited about making electronics smaller. Centralab was apparently less excited. In May 1958, Kilby left Centralab for Texas Instruments with a mandate to miniaturize.

As a new employee, Kilby had not accrued sufficient leave to enjoy the companywide two-week summer vacation. He instead used the time to sketch ideas for semiconductor-only circuits.

When vacation ended, Kilby made good progress with the help of technicians who could fabricate his designs.

By September 12, 1958, Kilby had the world’s first working integrated circuit. He had been at the company for about one hundred days.

Kilby’s invention paved the way for everything in electronics that followed: microprocessors, smartphones, the internet, artificial intelligence, and whatever is next in computing.

Kilby was recognized with the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2000, almost half a century later.

The more important recognition took place in early 1958 when Willis Adcock, then a manager at Texas Instruments, offered Kilby a job.

Institutions, and the people who create and manage them, make or break breakthroughs.

The Endless Frontier is dead, long live the Endless Frontier

President Franklin D. Roosevelt understood that science and invention were essential to winning World War II. Roosevelt tasked Vannevar Bush with developing a plan for supporting science after the war.

Why should US taxpayers support science?

Harry Truman, who became president after Roosevelt died, received Bush’s now-famous report, Science: The Endless Frontier. Bush’s answers were clear: Science is needed to create new weapons for war, and wage war on disease. The government, with public support, should fund foundational research. Universities should train scientists. Industry should commercialize academic discoveries and take forward innovation.

The nation will prosper.

Vannevar Bush’s model powered American science and innovation for seventy-five years. But scientists today, learning of his memo for the first time, often make a critical mistake. Scientists believe that Bush’s memo was written for them. And what scientist wouldn’t love such a framing?

Science actually is an endless frontier: discoveries create more questions; science seems infinite. But Bush’s memo was written for an audience of one—the president—and by extension the American public supporting him.

Bush’s memo worked until it didn’t. In early 2025, President Trump proposed funding cuts for science to levels not seen since 1975.

How could that have happened?

In 1989, the Berlin Wall fell. Absent a Cold War, the Hobbesian justification for public support of science (i.e., war) began to erode.

In 2005, John Ioannidis published “Why Most Published Research Findings Are False.”

In 2016, Nature, a top science journal, claimed that 70 percent of researchers had tried and failed to reproduce the work of other scientists; few stopped to ponder that a potential 30 percent success rate in reproducing frontier science and innovation might be extraordinarily awesome.

In 2019, SARS-CoV-2 emerged. Because building viruses from scratch became routine sometime in the past fifteen years, everyone could wonder whether the virus emerged from nature or a lab. What if scientists, in waging war on disease, had instead created disease?

Thus war on disease as justification for public support of science had taken two hits: reproducibility and responsibility.

And the politics of supporting science, grounded in war and war on disease, had changed. Yet the institutions and leadership of science had not.

As Hoover historian Stephen Kotkin put it to me in April 2025: “The Endless Frontier is dead. Come up with something new.”

Re-Genesis?

In November 2025, President Trump launched the Genesis Mission by executive order, declaring, “From the founding of our Republic, scientific discovery and technological innovation have driven American progress and prosperity. Today, America is in a race for global technology dominance in the development of artificial intelligence (AI),” adding that “in this pivotal moment, the challenges we face require a historic national effort, comparable in urgency and ambition to the Manhattan Project that was instrumental to our victory in World War II.”

Maybe a race with China will provide sufficient political justification to support science in America with the urgency and at the scales needed.

I fear it won’t, for three reasons.

First, the Manhattan Project cost about $2 billion in 1940s dollars, or $40 billion in 2020s dollars. If scaled to a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP), a Manhattan Project–level effort today would deploy at least $120 billion annually. While the Genesis Mission gets a lot of things right, starting with a clear call for the Department of Energy to act with urgency and in new ways that are more relevant to twenty-first-century science, it is unclear that Congress will appropriate new money at the scales needed.

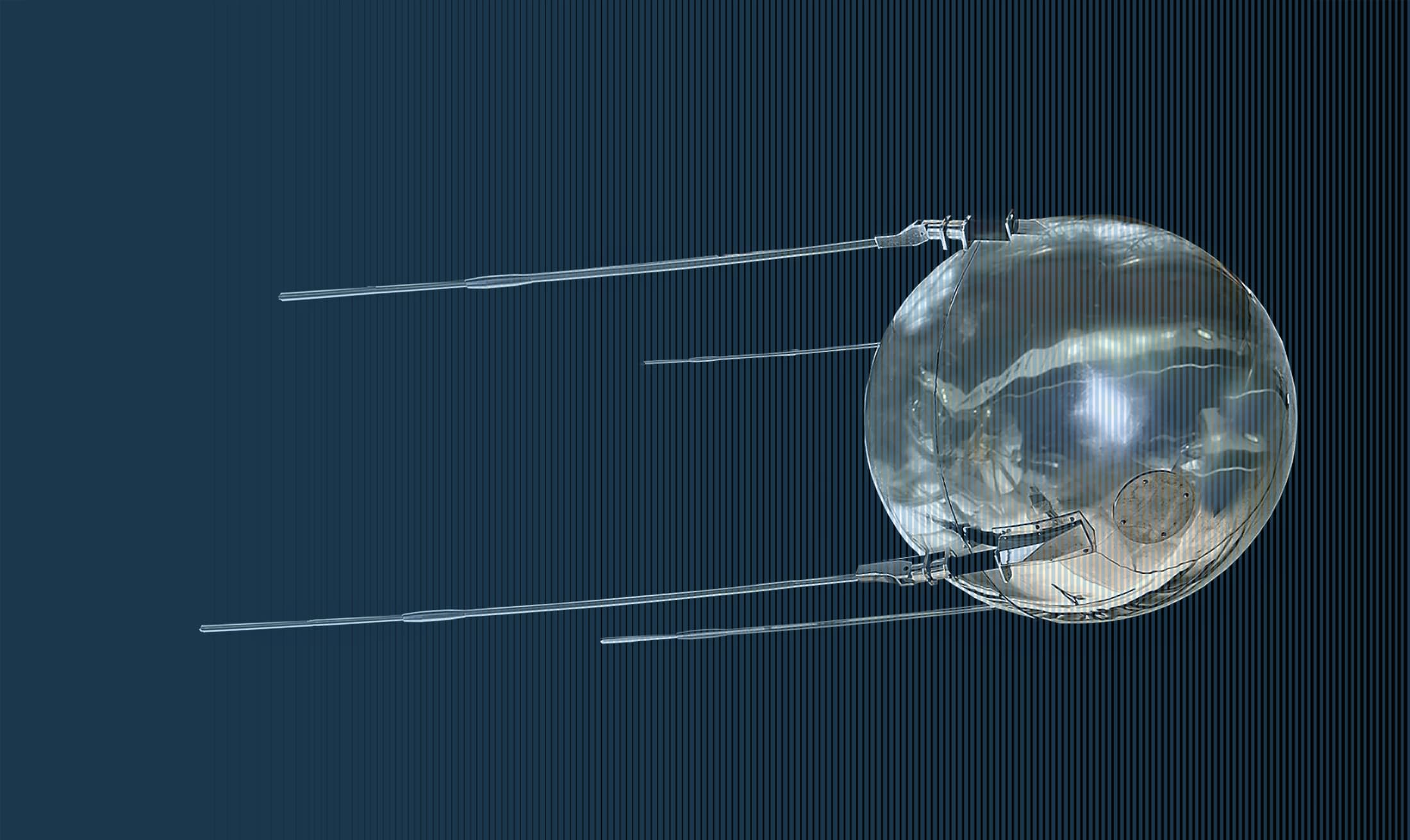

Second, Beijing may be savvy enough to avoid charismatic “saber rattling” and head-to-head competition in science sufficient to trigger a Sputnik-like response. In a context where China has already been building national labs from scratch, purpose built for twenty-first-century science, it is already easy for Chinese scientists and leaders to exclaim, “Why are you Americans making science so political? We are just trying to better understand the universe to make things work well enough to survive and prosper.” In this context, Congress and the American people seem more likely to be lulled into partial actions and regulation-only strategies.

Third, AI isn’t everything. Not even close. To a nerd, reality operates in three dimensions, not two; joules, bits, and atoms (energy, information, and stuff), not just joules and atoms. Yes, AI matters (a lot!) but AI will never be or become everything that matters.

Biology is the new silicon

For example, biology operates at the intersections of joules, bits, and atoms. Biology already harvests over 100 terawatts of energy; improving photosynthesis just a bit would unlock tens of terawatts of new energy production.

Biology has already taken over the planet—green goo! Biology assembles atomically precise structures at macroscopic scales—trees! Biology makes brains that instantiate actual intelligence using just tens of watts.

What Jack Kilby kicked off with the integrated circuit will be dramatically complemented by—if not transcended by—what bioengineers realize with DNA this century.

Having learned how to read and edit DNA, we are finally learning to write in As, Ts, Cs, and Gs. Beijing understands this. Biology is not one of many emerging technologies in China; biology is among the big three emerging technologies in China, along with energy and computing.

Why? Beijing has a reality strategy: how to provision what people physically need at scale. Energy, knowledge, and stuff. Biology operates at this intersection of joules, bits, and atoms and unlocks what we want there. Growing computers? Yes, someday, if we unlock biology as a general-purpose technology.

Biotechnology is also how to secure a reliable food supply on a changing planet. Ditto for medicines, materials, explosives, and anything else bioengineers can learn to encode in DNA. Ditto for securing biology itself, creating a deterrence-by-denial foundation for public health and biodefense.

So, it should be no surprise that about half of the five thousand students competing in October at the global genetic-engineering olympics in Paris were from China. Or that some students in California find it easier to join genetic-engineering teams in Beijing than in San Diego. Or that the Shenzhen Institute of Advanced Technology, with a special focus on synthetic biology, is now the model for state-backed research, combining scale, speed, and ambition in ways that echo Cold War–era America.

Ideas for the new frontier

What lessons does 1931 Dallas offer us today?

New beginnings rarely look like destiny. A truck for oil exploration led to the integrated circuit only because of war, urgency, vision, agility, and leadership.

Somewhere today—in a community bio lab in Colorado, a garage in San Diego, an institute in Shenzhen—innovators are inventing a living future more wondrous than can be readily explained.

Jolted by Project Genesis, American science finally has a chance to begin to get unstuck from our 1950s-era institutions, preciousness, sublimation of urgency, and politics. But then what?

We must double down on the ambition and agility embedded within Project Genesis. We must especially expect and support that major institutions within our scientific enterprise should change over time, sometimes dramatically.

What if national labs ran on ten-year missions? Each lab would be up for grabs once a decade. New teams would propose bold new ideas most relevant to the nation and compete. Teams could compete for a one-time extension, but that’s it. These would be term limits for big science teams, baking in evergreen agility and relevance.

What if public funding for small science, the sort of work done by individuals, dropped most of the paperwork? Today, many taxpayer-funded researchers spend most of their time just trying to raise a few hundred thousand dollars, not in doing the actual science. Instead, we should adopt and scale practices like those pioneered by the Hypothesis Fund, which empowers and tasks excellent scientists with giving money to other scientists whose work they believe will be particularly impactful—this is positive peer accountability and community support instead of zero-sum committees.

We should also recognize and celebrate that the primary job of a PhD student is not to discover or invent something; those are byproducts of a great PhD. Instead, a PhD student’s number one job is to become better at science, at choosing what to work on and when to change projects. What this means is that funding for PhD students should go to PhD students directly in the form of many more federal fellowships.

Finally, let us finally acknowledge a “secret” every scientist knows but not all admit. The tools of science are more important than anything else. How we measure, model, and make is more important than being smart and hardworking (and yes, being smart and hardworking are incredibly important). Restated and practically, for every dollar spent on doing science, five cents should go for improvements in the tools used to do science. Sustained improvements in these tools are the only way to guarantee leadership in science and the resulting technologies.

Changes like those above can help all Americans reimagine what is and can be great about uniquely American approaches to science.

Let’s go!

One more thing

But what about the money? What about justifying science to the American taxpayer? Yes, the theme of war on disease could be revived, but it would be foolish not to take advantage of the current moment to better understand what changes most Americans wish for with respect to health and medicine. Hopefully, global war never returns, so let’s not count on that as a justification. Bilateral competition with China? Maybe? But science is too important to bet the farm on that framing (plus, no one likes to lose).

What about higher goals that are simply positive? What about something that is not zero sum, such as economic growth? What about bringing America together by enabling Americans to make money together? What about freedom? What about combining freedom with economic growth? What about promising—and making real—that advances in science and technology will advance not only life but also liberty and the pursuit of happiness? How? By ensuring that the translation of discoveries and inventions into technologies gets the terms and conditions right. And so on.

We can invent and make real a prosperous and positive future for science in America. Doing so requires more sophisticated thinking and practices than what worked before. Now let’s go!

The new report Biosecurity Really: A Strategy for Victory emerges from the Hoover Institution’s Bio-Strategies and Leadership group and was led by its chairman, Hoover science fellow and senior fellow (by courtesy) Drew Endy. Professor Endy also researches and teaches bioengineering at Stanford University, where he is the Martin Family University Fellow in Undergraduate Education, senior fellow (courtesy) of the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies, and faculty codirector of degree programs for the Hasso Plattner Institute of Design.