People often reach for bad historical analogies when they are bewildered by the present. But the present Venezuela crisis offers a new wrinkle. Having apparently drunk deeply from the well of myths about supposed American imperialism, the Trump administration, thus intoxicated, engages in a kind of cosplay pretending to emulate the imperial strutting of William McKinley or Theodore Roosevelt.

Like so many cynics or anti-American critics, they are evoking a version of American history that is just wrong. No, the Trump intervention in Venezuela is not much like earlier US diplomacy in the Caribbean Basin. William McKinley had no wish to intervene in Spain’s war in Cuba; his involvement in the Philippines was even more reluctant. In every possible way, McKinley’s style was the utter opposite of Trump’s.

Nor do current US policies much resemble those of Theodore Roosevelt. TR faced quite difficult dilemmas in that era’s Venezuelan crisis (the country facing a German and British blockade accompanied by declarations of war), or over whether and how to build a Panama canal, or picking a path amid the chaos of Santo Domingo.

That era’s interventions were dominated by real concerns about foreign intervention to collect debts from bankrupt governments torn by coups and civil violence. One of the US policy’s principal architects, Elihu Root, was also a founder and first president of the American Society of International Law. He was conscientiously devoted to its practice.

American power in a clearer light

Amid so many tendentious accounts, it is fortunate that there are good, reliable histories of US policy in this older period. There are careful older works by Dana Munro, a fine scholar and knowledgeable ex-official, published in 1964 and 1974. More recently there is Sean Mirski’s excellent book published in 2023.

Munro and Mirski both observe how remarkable it was that, just when US power in the Caribbean Basin was at its height, in 1919, after the First World War and the threat of foreign intervention had disappeared, that the United States chose to start gradually disengaging from the region. By the 1920s, American leaders concluded, on their own, that they had destabilized the region in their predecessors’ increasingly clumsy efforts to stabilize it. In the Coolidge administration, the new model of American relations was set, in the most important case, by Dwight Morrow’s mission to Mexico, a masterpiece of diplomacy working to accommodate Mexico’s gradual state takeover of American oil interests.

Persistent beliefs about American imperialism in Latin America are “not surprising,” Munro wrote, “because the same ideas about the motives behind the intervention policy have often found expression in the United States. . . . Writing at a time when historians were prone to assume that all governments were unprincipled and that governmental actions must be explained by economic considerations, ‘anti-imperialist’ authors assumed that the United States could only have been acting for the benefit of American financial interests.”

The record of American interventions “might have been forgotten after the repudiation of the intervention policy by Presidents Hoover and Franklin Roosevelt, had it not been for the belief that the policy was inspired by sinister and sordid motives, which might well reassert themselves at some future time.”

Welcome to “some future time,” when a president might resurface the fear of “sinister and sordid motives.”

Instead, there is the real historical record. This, as Mirski recently summed it up, was that “Officials in Washington had no premeditated plan to reduce the whole region to vassal status. As impressive as the number of American interventions is, the more revealing figure is the far greater number of times that Washington declined its neighbors’ invitations to send troops, annex territory, or establish protectorates.” (Emphasis in the original.)

In that era, Mirski adds, there were no great cultural, personal, or ideological motives at work. Such explanations “fit poorly with the often extreme reluctance of American officials to use force in the region.” And, “on balance, racism . . . likely curbed American adventurism.” It “led most Americans to want nothing to do with the region, which in turn dampened their enthusiasm for intervening in it.”

Also, “for all its polemical appeal,” Mirski found that accounts of America as “a muscleman for Big Business” are similarly exaggerated. “[E]ven when American companies were directly involved, it was not unusual for the government to neglect, oppose, or even double-cross them. Simply put, Washington was usually after bigger game than bananas.”

Analogies to the more recent US invasion of Panama, in 1989, are similarly misplaced. When the Panama crisis came to a head in 1988 and 1989, I had a good window, as a career diplomat and NSC staffer, on how that crisis and war developed. Other leaders in the region understood who General Noriega was. They understood and mostly welcomed the US confrontation with him. They respected the civilian president who took his place and was elected to office. Panama’s military dictator, whose national assembly had declared war on the United States, justifiably ended up serving time in US, French, and Panamanian prisons.

The view from the Western Hemisphere

The Western Hemisphere has again become important. That point was recognized as soon as the Cold War was ending. That recognition, between 1988 and 1992, drove the wise original impulse to build up the prosperity of North America as a whole. Today, well into the twenty-first century, the Western Hemisphere should still be a top priority for the United States, especially the security and combined prosperity of North America.

Accepting that premise, I offer four assertions about the present crisis.

1: The Caribbean Basin is not the Western Hemisphere.

The United States has very active policies in the Caribbean Basin. Grandiose assertions about the Western Hemisphere are another matter. The Western Hemisphere covers half the globe. The Trump administration does not have a meaningful strategy for the “Western Hemisphere.”

In its own pronouncements, the Trump administration’s principal US interests in the Western Hemisphere are to pursue policies that keep turmoil, migrants, and crime away from the United States. These interests seem to have little to do with most of the Western Hemisphere. That disinterest is evident.

Looking around the world, the president has a long list of people he regards as naughty and nice, a list moodily and frequently revised. In the case of the Western Hemisphere, Trump inherited a friendly leader in Argentina. He further alienated the unfriendly leader in Brazil. He helped produce a less friendly leader in Canada. He had already (in his first term) helped produce a less friendly leader in Mexico.

The top US interest in the Caribbean Basin, or even the vastly larger Western Hemisphere, should be the stability and cohesion of Mexico. With an ancient civilization and more than 130 million people, Mexico is America’s largest trading partner. Its prosperity can help our own; its problems spill over.

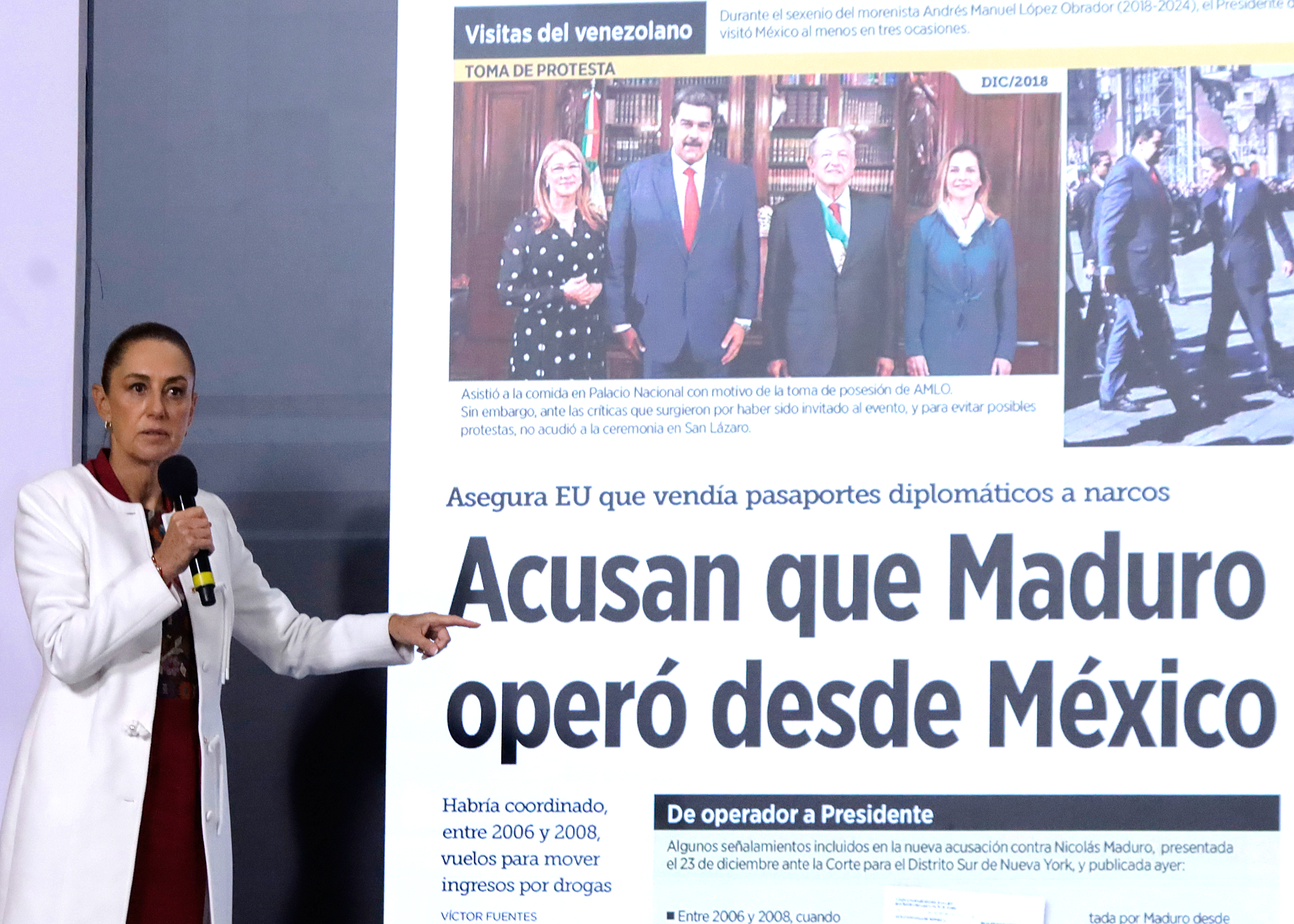

Mexico’s governance and condition deteriorated in the administration of Andrés Manuel López Obrador (2018–24), which adopted self-defeating energy policies and damaged cooperation against transnational criminal cartels. The situation has become quite serious. Some Mexican experts fear that a significant fraction of their country is now governed in partnership with criminal enterprises.

Aided by a capable US ambassador in Mexico City and a knowledgeable former ambassador as the deputy secretary of state, the Trump administration is fortunate in the quality of partners it has found in the successor administration of Claudia Sheinbaum. The US government has made some quiet headway in Mexico. It can build on the Mexican government’s own unease about a tidal surge of Chinese imports. The current renegotiation of the US-Canada-Mexico trade agreement will be a decisive test.

The Venezuelan fireworks do not help. Sure, one can bluster that the Mexicans will now have even more reason to fear US strikes into Mexico. Those strikes will yield little, and turn counterproductive, if the United States does not have good eyes in the field, in Mexico, working with Mexican authorities. The Mexican government knows this too, as it juggles its suspicions of the United States with its own anxieties about the growing power of the cartels.

2: There is no evident strategy to turn around Venezuela.

The economic collapse in Venezuela produced millions of refugees, about a quarter of the population. It can get worse. With his military buildup during the past six months, President Trump created a situation where he had to act yet could not act well.

Confronting a genuinely serious problem, President Trump and his team did not have the patience or ability to organize a serious response. He did not put in the work to make a sustained political case, to bring Congress along, to organize quite substantial civilian and commercial help, or to muster a serious regional coalition. He built no political or material base for a difficult and sustained American effort to restore capable governance to Venezuela.

Lacking such a base, the president could either give up or ask the special operations forces to pull off a coup de théâtre to capture Maduro. This they did. It was an impressive performance, from forces specially trained to do it. It was a close call. If Venezuela had possessed an arsenal of even mediocre armed drones, the US helicopters—slow and not the least bit stealthy—would have been easy targets.

It was also a one-off. Future military moves will have to rely on blowing things up or putting many troops on the ground. With Maduro in jail, the thin legal basis for such American actions in Venezuela gets even thinner. Now the president must try to make some deal with the dictatorial regime he leaves in place.

The president invokes the role of major oil companies in rebuilding Venezuela. That reasoning is about an inch deep. The leaders of actual major oil companies, like Chevron, are careful people steeped in the difficulties. They prefer lasting partnerships with those who live in the faraway places. They may coach the administration, but when they paint pictures of Venezuela’s potential future, pictures Trump then relays in his way, they know very well that it is committed Venezuelans who will have to make these visions of sugar plums real.

The companies know, for example, that there are some buyers eager to refine Venezuelan oil and take the place of Chinese buyers. But the Venezuelan regime will insist on getting its cut. If the regime gets its cut, it can sustain itself.

A strategy to turn around Venezuela would have to include some substantive concept for how the country would be secured and stabilized, curbing transnational crime beyond just expelling some Cuban advisers.

A strategy to turn around Venezuela also would have to include some serious concept for economic renewal. Nearly a decade’s worth of policies and institutional changes brought Venezuela to ruin in the first place. The Trump administration cannot yet even articulate a coherent story for how the Chavista regime might reinvent itself.

Secretary of State Marco Rubio and his team are frantically improvising, and it shows. The situation is not hopeless, but it is formidable. If, somehow, Venezuelans and knowledgeable Americans can devise a strategy that shows real promise, that could have a payoff not just in Venezuela but in Cuba too, another country on the brink.

There are precedents where foreign governments, including the United States, have taken effective control of another country’s revenue. In the past this usually happened through control of the customs revenue. This was usually done to be sure that foreign debts were paid. In this case many of the debts—mainly to China—are more likely to be repudiated. Perhaps some American claimants and bondholders think they will move up the queue for payment.

There are no good precedents of using foreign control over revenue to force successful local implementation of meaningful political and economic change that broadens the base of governance and prosperity. American practice from the early twentieth century is not encouraging. Instead, the foreign power tends to rely on and reinforce some local dictatorship. Sometimes it even has to send in its own forces to support a protectorate, but Trump has not built a political base to do that.

3: There is no evident strategy to knock back the transnational criminal cartels.

The transnational crime cartels are a very serious problem whose operations have frequently spilled over into the United States. Though Americans focus only on neighboring criminal networks, they are among the victims of giant criminal syndicates based in southeast Asia. Few Americans have noticed that our neighboring networks help support the criminal networks now menacing Europe to an unprecedented degree, networks linked to violence-torn areas in the Mediterranean world and the slums of European cities. It is hard to detect a coherent whole-of-government strategy to set this back.

President Trump’s symbolic performances cut both ways. With one hand, he has used the American military to apprehend the Venezuelan president, accused of abetting drug trafficking. A month earlier, with another hand, President Trump pardoned the imprisoned former president of Honduras, who was shown in court to have played a critical part in a massive international criminal operation.

President Trump has also used special operations forces to destroy drug boats. But these efforts only supplement the larger-scale and longstanding interdiction efforts of regular Coast Guard and police forces. Meanwhile the strikes alienate traditional partners who provide the United States with intelligence and assistance in combating the drug trade. Some have now cut back on this cooperation. There is no evidence that the added strikes have impacted the net flow of drugs into the United States or Europe. Venezuela is not an important source of drug trafficking into the United States.

Meanwhile, as the United States has further destabilized Venezuela, it has undermined cooperation and potential progress in neighboring Colombia, a country much more important in a strategy to fight the cartels. One Colombian police colonel recently commented that “[Colombian] President [Gustavo] Petro is not popular in the security forces, that is no secret. But he is not a drug trafficker. The US broke agreements that had been signed, withdrew money that had been promised, humiliated our country and president, and then pardoned convicted drug traffickers for political reasons. The US is no longer a partner we can trust, and this hurts me deeply to say it.”

4: As some US officials scorn international law, the United States relies on it.

The Trump administration regards disdain for international law as a point of pride. It is therefore worth taking a brief look at the ongoing American seizures of tankers that have been so much in the news.

The US government relies on international maritime law to go after these ships. They are regarded as part of vast “shadow” or “ghost” or “dark” fleets of ships that are unregistered or fake their registration, disguise their locations, and conceal their ownership. The rise of this vast merchant fleet is an aspect of the global conflict and sanctions enmeshing Iran, Venezuela, and then Russia, with other small players like North Korea and Yemeni Houthi rebels. The “shadow” fleets now deeply involve China as well.

In effect, the United States and its allies are waging a maritime commercial war against these nominally stateless vessels. We could think of these vessels as modern-day pirates, but they are not predators, they are the lifelines of commerce of enemy states. The naval war against them is seizing millions of barrels of oil, which can then be confiscated and sold under the twenty-first-century versions of prize law.

Britain and other European countries have already been using international maritime law to escalate their actions against “shadow” fleets, which have also engaged in covert warfare in the Baltic Sea and beyond against states that are helping Ukraine fight Russia. When the large, empty tanker called the Bella 1 was boarded and seized by US forces in the North Atlantic, the British government provided assistance in part because the vessel was already engaged in activities the United Kingdom regarded as unlawful, not just because the British had a view about US policies in Venezuela.

One of the engine rooms of the US maritime war is the Threat Finance Unit of the US Attorney’s office for the District of Columbia, which began this work during the Biden administration. The moves rely on various kinds of legal grounds, including the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, which the United States has not ratified but, at least until the Trump administration, has been regarded as a valid statement of customary international law.

Some European states have been reluctant to act against “shadow” vessels. But, as a British-based expert put it, “The US has pierced this veil of uncertainty regarding whether these actions could be lawful. And the drive that the US has been really showing in boarding these vessels, intercepting them, proceeding with the seizures might create a precedent for greater action against the shadow fleet.”

The implications are significant. If some US officials will temper their dismissals of international law, they can see how the mix of international and domestic law both empowers US forces and enables cooperative action against transnational criminal networks, from those that are private to those that work with or are directed by hostile states. If, on the other hand, US officials contend that it is strictly a matter of power, not law, the United States will undermine its ability to muster the allied support it will need, from countries like Japan or in Europe, if it confronts a maritime crisis in a case of the first importance, near Taiwan or in the South China Sea.

Power misspent

Amid all the sound and fury, President Trump and his administration have basked in an imperiousness that evokes a false version of America’s past. They have not yet developed strategies likely to serve their own priorities. Some of the more interesting experiments validate legal frameworks and cooperative strategies that some of the administration’s officials affect to despise.

In the Caribbean Basin, as in parts of southeast Asia and the Mediterranean world, the world confronts catastrophic misrule, ill-governed spaces, crime networks of unprecedented scale, and yawning gaps between traditional norms of law enforcement and the warlike measures that may be needed. Measured against that challenge, so far, the Venezuelan crisis of 2026 shows how a great power can seem small. And yet, it is not too late to recall some real elements of American greatness.

Philip Zelikow is the Botha-Chan Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution, where he co-leads the Hoover History Lab and participates in Hoover’s George P. Shultz Energy Policy Working Group, the Applied History Working Group, and the Global Policy and Strategy Initiative. For twenty-five years he held a chaired professorship in history at the University of Virginia, where he also directed the nation’s leading research center on the American presidency. Zelikow focuses on critical episodes in world history and the challenges of policy design and statecraft.