Policymakers and voters care about reducing inequality and poverty, although they have historically disagreed about how to do this. In recent years, though, higher minimum wages having emerged as one of the most—if not the most—politically popular approaches to supporting low-wage workers and low-income families.

While the federal minimum wage has been $7.25 per hour since 2007, thirty-one states and the District of Columbia now have minimum wages above the federal level, in many cases much higher. The average state minimum wage in these jurisdictions now exceeds the federal minimum wage by around 80 percent, and minimum wages go as high as $16.90 in California and $17.95 in the District of Columbia. While minimum wage hikes have historically been more aggressive in liberal states and cities, they have spread to other places like Arkansas ($11), Florida ($14), Missouri ($15), Nebraska ($15), and South Dakota ($11.85).

Moreover, the minimum wage is likely to have increasing policy salience in the coming years, playing into broader themes emerging in the run-up to the 2028 presidential election. “Affordability” is already emerging as a central theme of the campaign, and policy debate is pushing higher minimum wages as a way to help address the affordability crisis. Moreover, with a rising populist streak in the Republican Party, both parties may soon converge on higher minimum wages as a popular platform, lessening restraints on even higher minimum wages.

Here’s the problem: minimum wages are ineffective at reducing earnings inequality, and ineffective at reducing poverty.

Where inequality lies

Turning first to earnings inequality, even before we turn to the evidence on the actual effects of minimum wages, it’s clear that we should not expect too much from the minimum wage. Research shows that the long-term rise in earnings inequality was pronounced in the upper part of the earnings distribution as well as the lower part. For example, the upward trend in the ratio of the 90th percentile of the earnings distribution relative to median trended up roughly as strongly as the median/20th ratio. Moreover, a substantial share of the decline in earnings at the bottom of the distribution is due to less time worked, rather than lower wages—a problem that higher minimum wages would likely exacerbate (as discussed below).

And perhaps the most dramatic rise in earnings inequality has come at the very top of the distribution—the top 1 percent or higher—which has nothing to do with the minimum wage.

Thus, at best the minimum wage could play a minor role in reducing inequality, and do nothing about higher inequality driven by the extreme upper tail—i.e., the rich pulling away from everyone else.

It’s hard to help workers when some lose their jobs

Moreover, research shows that higher minimum wages have adverse effects on some workers that offset any wage gains engineered by the policy. A higher minimum wage raises the cost of low-skilled labor to companies. This leads them to cut back on using low-skilled labor for two reasons:

· First, they have an incentive to substitute toward other inputs, such as higher-skill labor or machines, to produce whatever they make.

· Second, the higher minimum wage raises costs, and hence prices of goods and services produced by firms that use more low-skilled labor, reducing consumer demand for the products of these firms.

Effectively, the minimum wage is a tax on hiring low-wage workers.

Empirical research testing this prediction has preoccupied economists for decades. The conclusion is contested, but the overall evidence clearly points to adverse effects of minimum wages on employment. There are some high-profile studies to the contrary, such as a famous study by David Card and Alan Krueger that compared minimum wage changes in the fast-food industry in New Jersey and bordering areas of Pennsylvania, before and after an increase in the minimum wage in New Jersey, and found that employment actually increased in New Jersey, with a positive elasticity of around 0.6. The study was controversial, and its findings, attributed to poor survey data collection, were overturned in research I did with William Wascher using actual payroll data.

The Card-Krueger study and a few others that do not find job loss are frequently touted by minimum wage advocates as the most credible evidence, and they have an outsized influence on policy debate. But as I have shown in research with other colleagues, some of this evidence is also flawed. In short, while still contested, I think the debate has been settled: minimum wages reduce jobs for less-skilled workers.

It is still possible that the minimum wage could reduce earnings inequality, if the wage increases for some workers offset the job loss (and hours declines) for others. But the evidence doesn’t back this up. Other research I have done indicates that once we account for job loss and hours changes, minimum wages don’t reduce earnings equality among lower-skilled workers because the employment and hours declines are substantial. Indeed, on average earnings of low-skilled workers decline, if anything—not a recipe for reducing earnings inequality.

What about poverty?

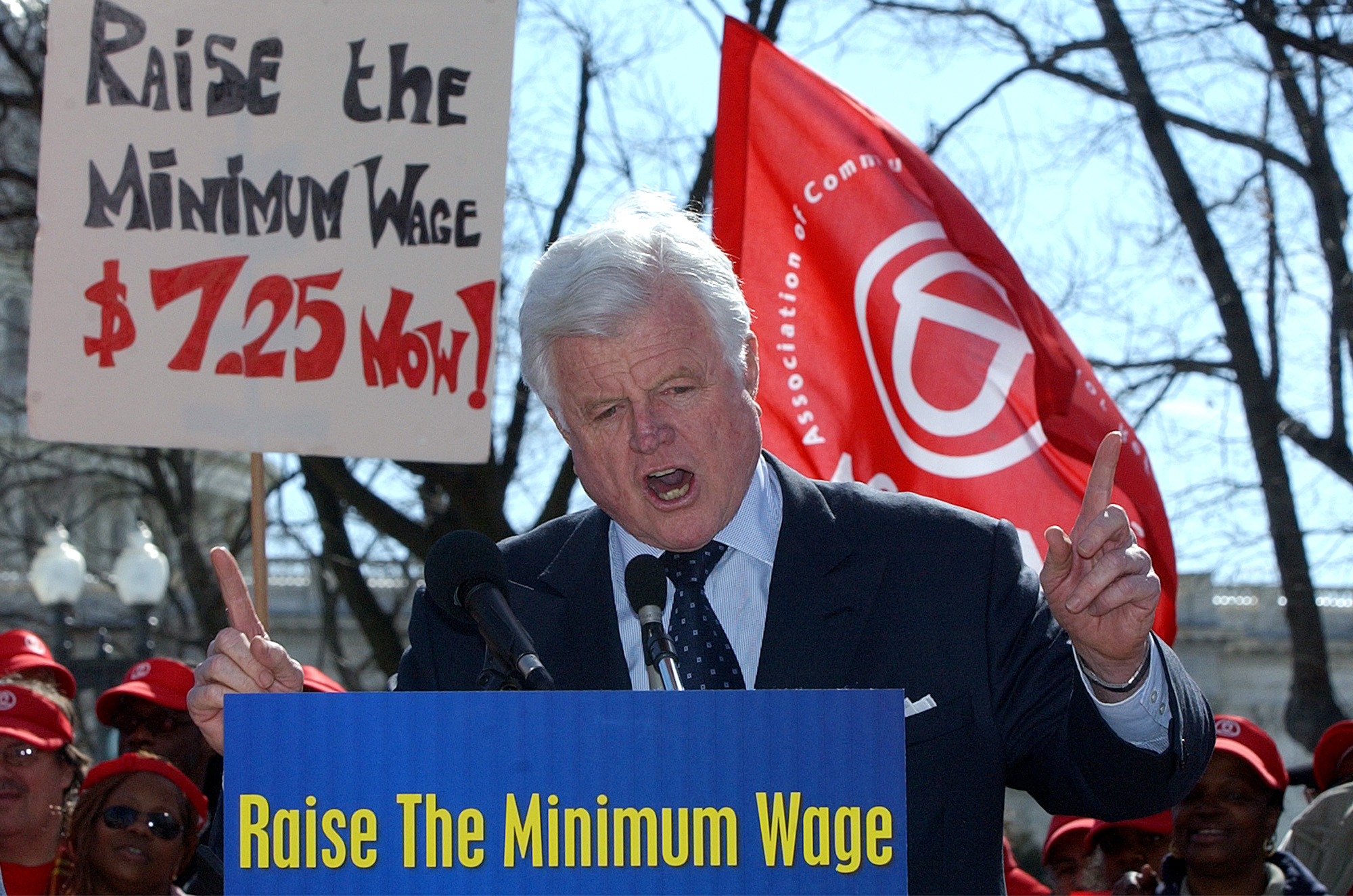

The second core argument for a higher minimum wage is that it reduces poverty. Indeed, Edward Kennedy, a perennial sponsor of higher minimum wages during his Senate career, argued that “The minimum wage was one of the first—and is still one of the best—anti-poverty programs we have.” The evidence against this position is actually overwhelming—providing a robust conclusion that the minimum wage has little or no impact on poverty (or other thresholds near the poverty line).

Indeed, it has long been understood that the minimum wage is a very blunt instrument to address poverty; even Card and Krueger, whose work is foundational for minimum wage advocates, recognized this, writing: “The minimum wage is a blunt instrument for reducing overall poverty . . . because many minimum wage earners are not in poverty, and because many of those in poverty are not connected to the labor market.”

The issue is that the link between being a low-wage worker and being in a poor family is weak; lots of minimum wage workers are teens in high-income families, and lots of poor families have no workers, or workers who work low hours. Thus, more so than for the evidence on earnings inequality, the evidence makes it very clear that a higher minimum wage is ineffective at reducing poverty. It doesn’t increase poverty; it just has an impact near zero.

There is one study that is a marked exception to this evidence, claiming strong effects in reducing the likelihood that families are poor or below other low income-to-needs thresholds. However, a recent re-evaluation of that paper makes clear that this one outlier paper suffers from having settled on just the right specification to generate evidence of poverty reductions.

Redistribution

The preceding evidence can be summarized simply as saying that the minimum wage performs badly as redistributional policy in the sense that it does not deliver benefits to the least well-off. But the minimum wage fails in other ways as redistributional policy.

First, those with the highest incomes do not pay for the redistribution that occurs via minimum wages. The first-order cost of a higher minimum wage falls on the owners of businesses that hire low-skilled workers. One might surmise—and many have speculated—that these business owners are in general not the highest earners. There is no such evidence for the United States, but recent research using detailed tax evidence from Israel confirms this. The owners of businesses that pay a large share of minimum wage costs have low incomes relative to other business owners, and similar incomes to higher-earning wage and salary workers.

It is a maxim of good public policy that those in similar circumstances should be treated similarly, and the minimum wage—in terms of who is paying for redistribution—violates this.

Second, employers pass through part of their higher costs from the minimum wage to consumers. And the evidence shows that, not surprisingly, the price increases fall on goods and services on which low-income people spend disproportionately—reinforcing the conclusion that minimum wages do not help the poor.

There’s a ready answer

This all sounds very discouraging. Inequality and poverty are problematic, and the one policy on which policymakers seem able to agree upon—and which sounds like an easy fix—either doesn’t help or exacerbates the problems. Fortunately, we have a much better, and tested, alternative: the earned income tax credit (EITC). The central challenge is to increase incomes of low-income families without discouraging work, and this is exactly what the EITC does.

The EITC supplements a low-income family’s labor market earnings by up to 45 percent up to a range, but pays nothing if the family has no labor income. It thus encourages work, and targets benefits well to poor families, most often going to households headed by single mothers. Research shows that it even helps families escape poverty before accounting for the EITC check. It also, as an additional benefit, appears to increase long-run earnings growth by boosting work experience. Note that all of these are the opposite of the effects of the minimum wage.

I would also argue that, despite a good deal of policy paralysis in Washington, even a major expansion of the EITC is plausible. The track record of adopting and increasing the EITC indicates that conservatives—with the exception of those opposed to any government redistribution—are supportive of the EITC because it incentivizes work, and liberals have supported the EITC because of how it redistributes income.

It is true that policymakers have to generate tax revenue to pay for the EITC, and they have probably been more enthusiastic about minimum wage increases because they do not need to raise taxes to pay for a higher minimum wage.

If the minimum wage were an effective way to reduce inequality and poverty, then in a context of aversion to expanding government programs it might be a reasonable policy to pursue, and perhaps the most feasible one. But because it is ineffective and still imposes costs (and the costs are not borne by those with the highest incomes), we should stop the endless cycle of increasing minimum wages and even consider unwinding them.

And if we actually care about those with low earnings and low family income, we have to pony up—and the most effective policy we have is the EITC.

David Neumark is a visiting fellow at the Hoover Institution and distinguished professor of economics and co-director of the Center for Population, Inequality, and Policy at the University of California, Irvine.