This article is part of Liberty Amplified, a recurring Freedom Frequency series produced in partnership with the Hoover Institution’s Human Security Project, featuring voices that challenge authoritarianism in pursuit of freedom.

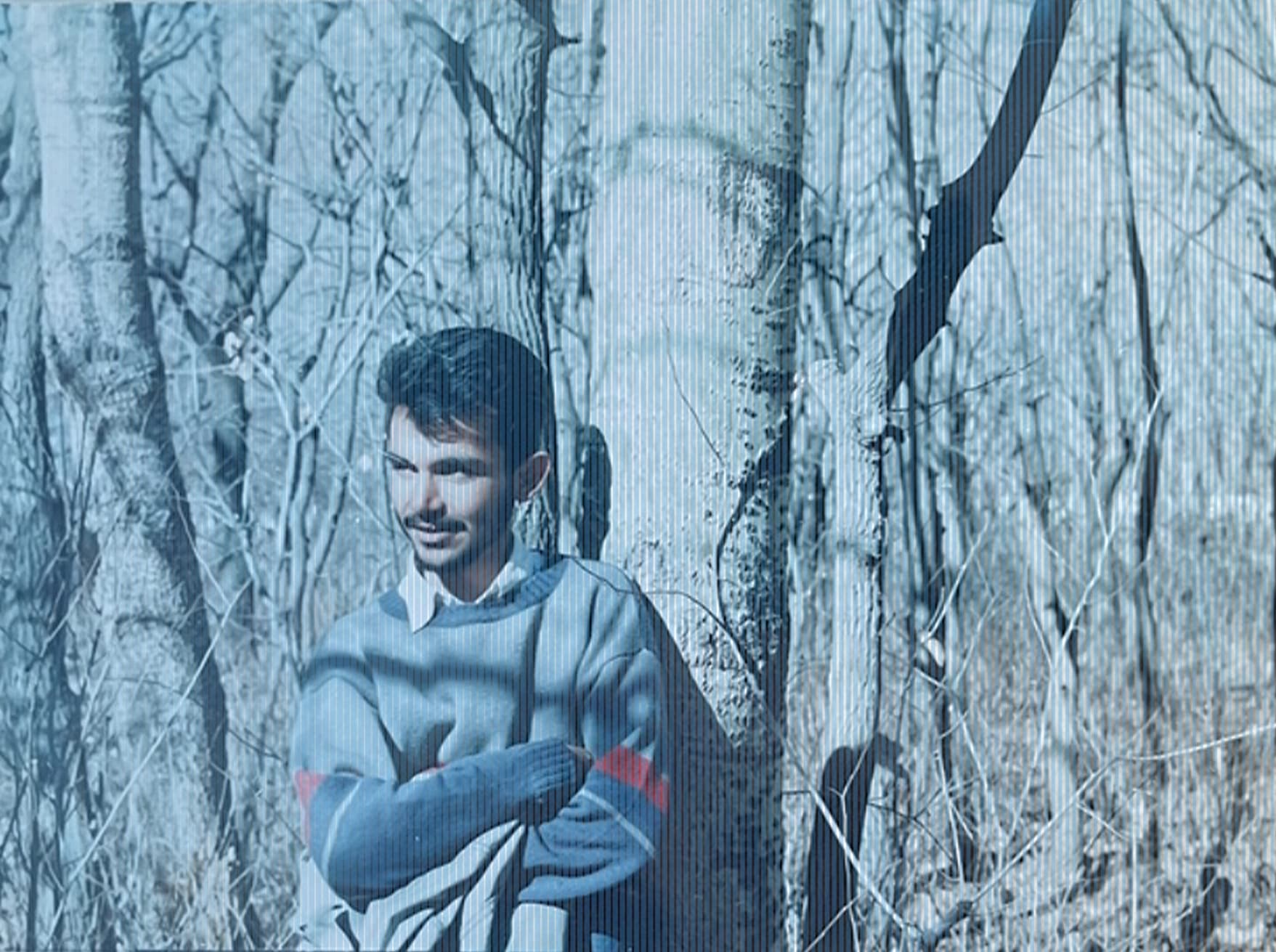

Qari Noor Agha wore a turban so large it seemed to swallow his narrow frame. His pale complexion came from years spent in dim madrasa rooms, “learning.” He was only fifteen years old—and he was my torturer.

I was bound in a damp, airless cell while he lashed the soles of my feet with electrical cables. The pain was sharp and searing, but I refused to scream. He paused, leaned close, and searched my face.

Confusion flickered in his eyes. There were no tears, no cries—none of the reactions he was accustomed to.

“He’s not even crying. Why?” he asked the others standing nearby.

They shrugged; they didn’t understand either.

He resumed, striking harder. Still, I stayed silent. My cries would give them joy, and I could not—would not—give them that satisfaction.

It was the autumn of 1998. I was twenty-three, imprisoned in a squalid facility in Maidan Shar, just outside Kabul.

As a student activist at Kabul University, I had often been a target. Like some of my friends, I refused to grow the long beard they demanded, spoke out against the expulsion of female students, and organized gatherings to discuss civil liberties and justice. With friends, I even slipped reports of human rights violations under the UN mission’s gate in Kabul, hoping to alert the outside world to what was happening. Those small acts carried great risk—and, eventually, a price.

In the prison, as the beating intensified, I closed my eyes and thought of my father, who had taught me the strength of silence in the face of this kind of pain. That lesson was now my armor. I could not hate my torturer; he was a boy indoctrinated into a system that promised him salvation through cruelty, a child who might face his own punishment if he disobeyed orders. I pitied him, even as his cables tore into my skin. Still, there was a certain eagerness in his strikes, a willingness to do his work well.

“Who are you working for?” he demanded between blows. “The US or the UN?”

“For none but our people” I answered. Always the same words, always making him angrier.

Two weeks earlier, I had been on my way to Kabul University when I was forced into a truck with three others. Mullah Nooruddin Turabi, the Taliban’s one-eyed, one-legged minister of justice, was present—infamous for public executions, stonings, and amputations carried out like spectacles in stadiums. When one detainee dared to ask why we were being taken, Turabi cursed him.

I didn’t know then whether my destination was a cell or a grave.

The prison consisted of two facing buildings with a muddy courtyard between them—and a basement where Qari Noor Agha plied his craft. Inside, cells overflowed with prisoners. There were no showers. The air reeked of damp and unwashed bodies. We slept huddled on tarpaulins for warmth. Our diet consisted of two meager meals a day: tea with a thin sliver of bread in the morning, and a small portion of potatoes at night. Red beans were a rare luxury. Afternoon prayers in the courtyard were our only reprieve. Between the closely timed prayers of asr and maghrib, we could see the sky. Tarpaulins kept us from kneeling in the mud, and then we were herded back inside to the soundtrack of other men’s screams echoing through the halls.

Seven weeks passed. One afternoon I was summoned by a guard. “Collect your things,” he ordered.

What things? The tarpaulin belonged to the prison.

The sun stung my eyes as I stepped outside. I climbed into a minibus, expecting to be sent to dig trenches for the Taliban front lines or to disappear into Kabul’s notorious Pul-e-Charkhi prison. Instead, I was dropped at Kote Sangi, on the outskirts of Kabul.

I breathed the dusty air of the chaotic city I called home and watched the mass of humanity going about its business. Street cart sellers calling the prices of their vegetables and the scent of fresh mint, a comforting and nostalgic fragrance for anyone who grew up in Kabul. The kids announcing the destinations of the minivans: “Cinema pamir wala!”

Most of those going about their day were men with long beards, looking gaunt and old before their time.

Even though I was no longer in prison, as I looked around, I realized that we were all prisoners in Taliban-controlled Kabul.

I thought of Qari Noor Agha—not yet a man, trained to believe cruelty was devotion. He had been told he was doing God’s work. Torture was his mission.

I survived, and I knew my mission was to make sure my country did too.

If he lived on, Qari Noor Agha would now be in his late thirties. By the time I found myself in official talks to determine Afghanistan’s future, it was entirely possible that he was high in the Taliban ranks.

And so, two decades after the day I limped out of Maidan Shar, I would walk into a different kind of room—not a prison cell, but a conference hall—where men in turbans and pressed waistcoats sat across from us. We were in Doha, and among them could well have been the boy who once beat me in a basement. This time instead of asking, “Who are you working for?” he would already know the answer.

Adapted from the prologue of Indecent Deal, a forthcoming book by Nader Nadery. Nadery is a visiting fellow at the Hoover Institution. He works with the Hoover Human Security Project, which pursues research into how authoritarian regimes sustain power and how those systems can be challenged to advance liberty. Nadery was a member of Afghanistan’s negotiation team for peace talks in Doha and also served as chairman of the independent Civil Service Commission of Afghanistan.

Liberty Amplified features the voices of those who defy autocracy in pursuit of freedom as part of the Hoover Institution’s Human Security Project (HSP). Led by Lt. Gen. (Ret.) H.R. McMaster, senior fellow at the Hoover Institution and 26th assistant to the president for National Security Affairs, (HSP) pursues research, generates actionable insights, strategies, and tools for understanding how authoritarian regimes sustain power and how pro-democracy groups and like-minded allies can challenge those systems to advance liberty. HSP serves as an educational resource and tool for activists in-country and those externally, promoting freedom and democracy.