This article is part of Liberty Amplified, a recurring Freedom Frequency series produced in partnership with the Hoover Institution’s Human Security Project, featuring voices that challenge authoritarianism in pursuit of freedom.

When Pastor Jin Mingri of Zion Church was detained in early October, Chinese state media cited “abnormal religious activities.” In truth, his arrest was ideological: Jin’s congregation of educated urban professionals and families represents a power Beijing cannot contain: faith-based solidarity independent of party control. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) sees religious communities’ moral autonomy as a threat to its grip on society, labeling them troublemakers and threats to social stability.

For decades, US policy toward China has been shaped by one fear: that China would descend into anarchy if the party collapsed. This fear mirrors the party’s own propaganda. In reality, China endures not because of its ruling party but despite it.

The fate of Christians in China is rarely a priority in American national security calculations; it is often assumed to be irrelevant to US interests. When the United States does condemn abuses—such as the imprisonment of Pastor Wang Yi—the action is morally right but rarely has any impact. Wang, the pastor of Early Rain Covenant Church in Chengdu, was detained in 2018 on charges of “inciting subversion of state power.” Despite strong pressure and numerous NGO campaigns, Wang remains in prison.

Beijing labels religion a domestic matter and considers such advocacy foreign interference, thus disregarding pressure from the West.

Sometimes, global advocacy helps a few prominent detainees escape to safety abroad. But for millions, overseas advocacy may offer solidarity but does not spark notable change in China.

Shepherds under siege

As a college student in 1989, Jin watched the tanks roll into Tiananmen Square—a crisis that shattered the certainties his generation held about secular ideals and opened his heart to faith. The Tiananmen massacre is widely seen as a watershed moment for Christianity’s revival in China. For many, the crackdown destroyed faith in political ideals, leading educated Chinese and youth to turn to Christianity for new sources of truth, hope, and moral guidance.

Like others, Jin built Beijing Zion Church to meet this spiritual hunger, expanding from living rooms, coffee shops, and rented office buildings into an influential “house church” (an unsanctioned faith organization in China).

At the same time, the party has long viewed religion as a relic doomed to vanish under modernization. For years, officials tried to bring Jin to heel, urging him to register under the official state church bureaucracy and to submit his sermons for the party’s review. He refused. Surveillance cameras appeared in the sanctuary; police raided services. Yet Jin kept preaching: “We must obey God rather than men.”

Even the COVID-19 pandemic didn’t kill the church. Services shifted online, reaching vast numbers. But “churching online” was intolerable to the CCP, leading to new rules in September 2025 that banned most online religious activities not sanctioned by the party—a clear move to reclaim ideological control over every sphere of Chinese life, including digital space.

Oppressed but resilient

Since its inception, the Communist Party has viewed Christianity as a destabilizing force that undermines party authority and opens doors to foreign interference. Yet, from Mao Zedong to Xi Jinping, every effort to stamp it out has failed. Christianity has flourished amid wars, famine, political purges, the Cultural Revolution, the Tiananmen Square massacre, and modern censorship. Today, Chinese Christians are estimated to number as high as 100 million.

In a regime obsessed with control, churches remain one of the last institutions the party cannot subjugate.

The party frames Christianity as “foreign,” but history disputes that. Before 1949, Chinese Christians helped shape modern China. They fought opium addiction, ran orphanages, founded universities and hospitals, pioneered women’s education, and advocated literacy among rural populations. Mission hospitals laid the foundations of China’s modern health care system. Christians served as diplomats and financiers who fought hard to advance the welfare of the Chinese people on the global stage.

Christians were pillars of China’s modernization long before the party claimed credit. Their contribution was indigenous, not foreign—rooted deeply in Chinese traditions and driven by Chinese believers. The CCP’s “sinicization” campaign—forcing Christianity into Marxist molds—bears no resemblance to that indigenous faith-building effort done by the believers themselves.

That spirit continues: Christians have led earthquake relief, set up food banks, opened counseling centers, advocated for suicide prevention, cared for “left behind” children of migrant workers, and assisted the disabled. Sociologists describe them as “social safety buffers”—offering compassion and care where the state falls short.

Yet, Zion Church’s noncompliance approach has prompted hesitation among house church communities. Critics fear it may trigger harsher crackdowns, affecting smaller churches with fewer protections. As a result, many house church believers find ways to expand religious autonomy quietly: negotiating with local authorities, meeting in less organized ways, avoiding publicity, and focusing on spiritual growth.

Beijing calls good men like Pastor Jin “troublemakers.” But they embody integrity, compassion, and moral courage who refuse to embrace the regime’s lies. They resist corruption and offer compassion in a culture of coercion.

In a frustrated society filled with cynicism, despair, and “involution,” where suicide rates rank among the world’s highest, Christians offer a genuine and patriotic alternative: trust, hope, and purpose. They stand on a moral high ground that the party’s slogans cannot match.

How to help America’s allies in China

Supporting China’s Christians is both compassionate and in the interests of the United States and other democratic nations. To make support effective, Washington should:

Recognize China’s faithful as allies. History shows that faith communities outlast authoritarian rulers and help rebuild nations. America should see Chinese Christians not merely as victims but as likely architects of a future post-authoritarian China. If the party’s grip ever loosens, China’s Christians will supply the same moral and civic foundation—rooted in faith rather than ideology—that holds a country together. Chinese people, including Chinese Christians, can be America’s allies, not enemies.

Adopt a long-view strategy. Religious repression may intensify; effective advocacy requires more than urgent diplomatic pressures and media concerns. Sustained evidence-based counternarratives to communist propaganda are needed.

Strengthen church links. US organizations with active China partnerships should receive greater support, especially in critical areas like humanitarian support, disaster relief, counseling, and entrepreneurship. These initiatives bolster the Chinese churches to serve and lead in times of crisis.

Defend freedom in digital space. As Beijing weaponizes artificial intelligence to enforce digital authoritarianism, the battle for digital religious expression is critical. Washington must champion free speech, digital rights, and AI ethics, holding regimes accountable when they manipulate technology to suppress beliefs.

In the end, embracing China’s religious faithful is not just an act of compassion—it’s a vital partnership for building a future China where liberty, trust, and human flourishing can thrive.

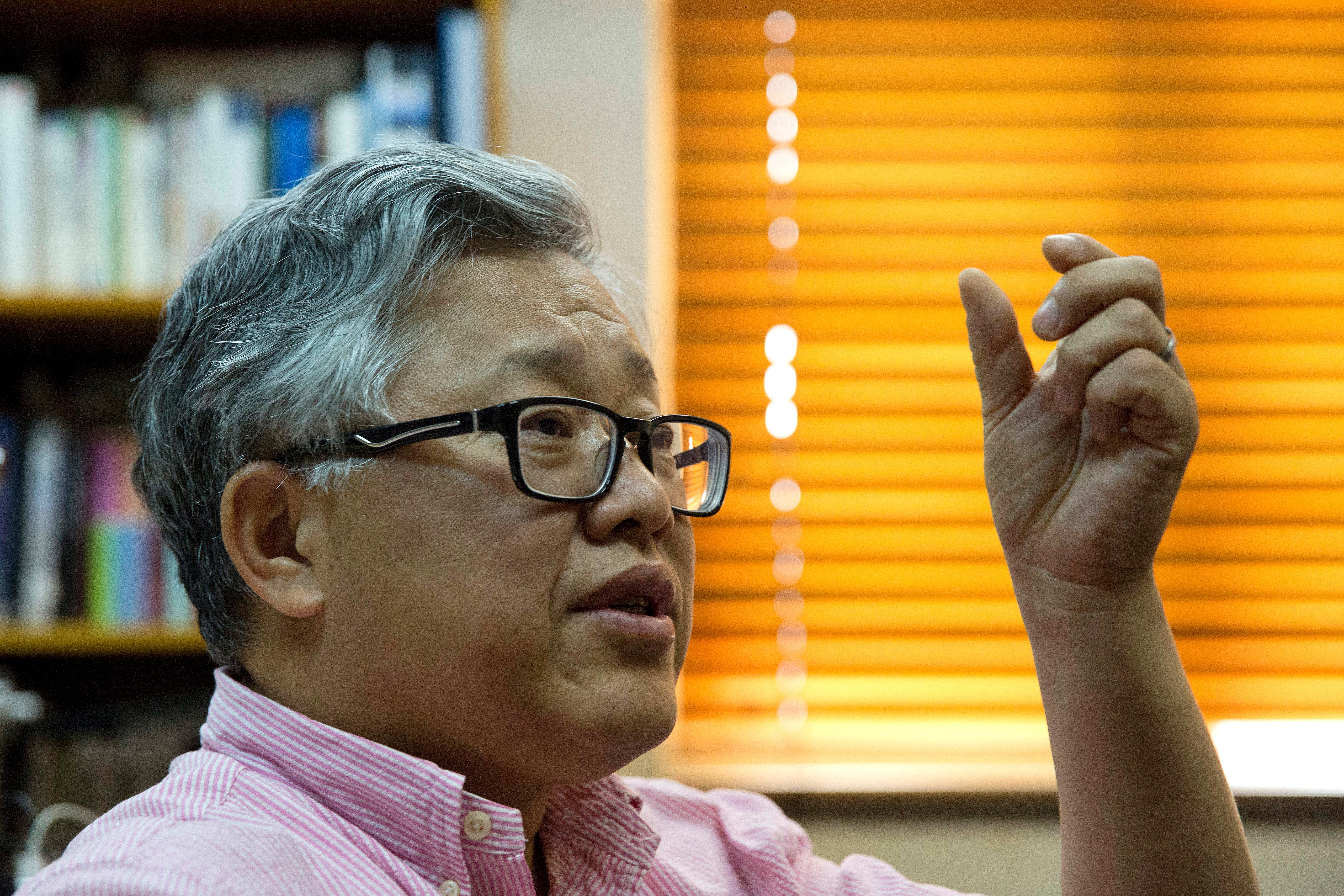

Elisa Zhai Autry is a research fellow at the Hoover Institution and contributes to the Human Security Project. Dr. Autry served as principal policy adviser on Global China and East Asia and Pacific Affairs in the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs at the US Department of State.

Liberty Amplified features the voices of those who defy autocracy in pursuit of freedom as part of the Hoover Institution’s Human Security Project (HSP). Led by Lt. Gen. (Ret.) H.R. McMaster, senior fellow at the Hoover Institution and 26th assistant to the president for National Security Affairs, (HSP) pursues research, generates actionable insights, strategies, and tools for understanding how authoritarian regimes sustain power and how pro-democracy groups and like-minded allies can challenge those systems to advance liberty. HSP serves as an educational resource and tool for activists in-country and those externally, promoting freedom and democracy.