This article is part of Liberty Amplified, a recurring Freedom Frequency series produced in partnership with the Hoover Institution’s Human Security Project, featuring voices that challenge authoritarianism in pursuit of freedom.

I woke early, rushed to the balcony, and watched the stars fade into dawn. The cold bit my face, yet something inside me felt warmer than ever. I kissed my wife and two sleeping children and hurried to catch the first bus. It was December 10, 1989.

That morning, I moderated the first unauthorized demonstration in Mongolia. Our demand was apparent: freedom—political, economic, and social. The unexpected spark ignited a revolution that ended seventy years of communist rule. Since 1990, Mongolia has been the only vibrant democracy between Russia and China. Against repression and authoritarian revival, our democracy continues to shine like a northern star across Eurasia’s uncertain skies.

A different path

Conventional wisdom says that in Asia, reforms begin with the economy, and politics and society liberalize only later, if ever. Mongolia proved the opposite.

We changed everything at once. Freedom of expression, private property, and human dignity arrived together, not in sequence. And remarkably, no blood was shed.

Our peaceful protests included marches, hunger strikes, blockades, and rallies. The driving force was young people whose demands came from the grass roots. By the time authorities tried to control us, it was too late. They had to negotiate, concede, and ultimately agree to constitutional change.

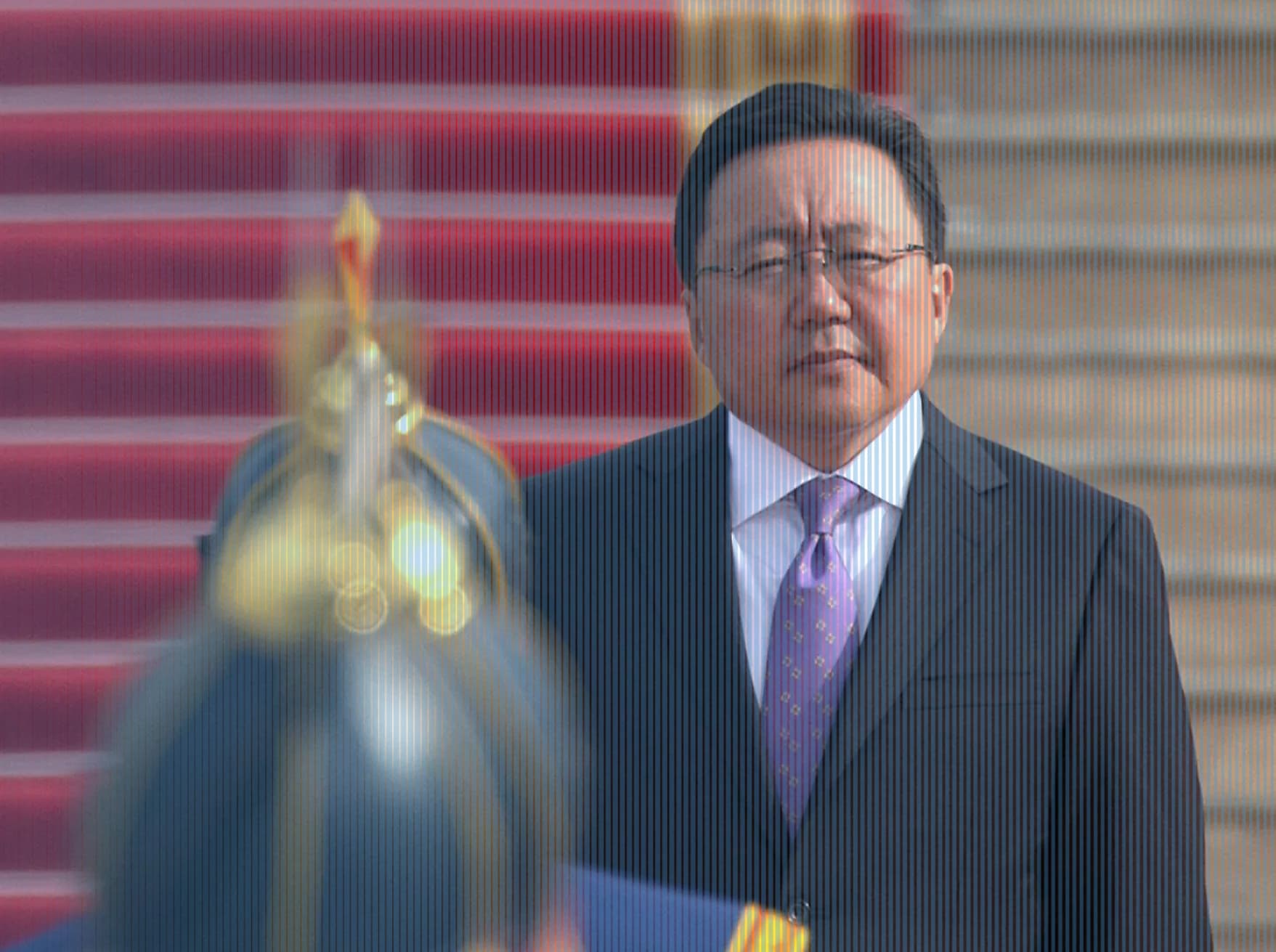

I am the son of a herder, one of eight brothers. I witnessed firsthand how ordinary people carried this transition on their shoulders. Later, I was fortunate to help draft our democratic constitution and even serve in government. I became prime minister at thirty-five, a title so unfamiliar that when I told my mother, she asked: “What is a prime minister?” She had only known Politburo members and general secretaries. Her advice was simple: “Be grateful to the people. Work hard.”

Many transitions in the late twentieth century faltered. Ours succeeded because the people themselves owned it. For us, democracy not only was about political choice, but it was the path to true independence. Mongolia was the second communist country after Russia, and the ideology of the 1920s consumed it. For decades, we endured purges, executions, and suppression of national identity. And yet we resisted.

Mongolia’s border stretches over 5,100 miles and is shared with only two neighbors: Russia and China. Few countries live in such a difficult neighborhood. These giants scrutinize every choice we make. Still, Mongolians have preserved self-rule. It comes at a price, but it proves that freedom is not a Western luxury but a universal calling.

People desire freedom

How does democracy survive between repression and dictatorship? My answer: resistance is always possible. Every human heart carries a seed of freedom. Even when crushed, it revives.

When I lectured at Kim Il Sung University in North Korea, I was told not to utter three terms: democracy, human rights, or market economy. I obeyed technically. Instead, I titled my lecture: “No Dictatorship Lasts Forever.” That cost me a meeting with the “Dear Leader.” Yet South Korean activists later picked up my speech, copied it, and floated it into the North by balloon. Words can travel farther than walls.

Several years ago, I spoke out when China banned the teaching of the Mongolian language and scripture. I reminded Beijing that the Chinese constitution guarantees minority rights. There are more ethnic Mongols in China than in Mongolia itself. True strength is shown in how a society treats its minorities.

In Russia, ethnic minorities continue to suffer disproportionately. During the Ukraine war, many have been sent as cannon fodder. I urged young Russians, especially Buryats, Kalmyks, and Tuvans, to escape mobilization and seek refuge in Mongolia. Tens of thousands did. If even one fewer gun is pointed at Ukraine, that is Mongolia’s contribution to peace.

History teaches us

Mongolians say, “The good in history is my teacher, and the bad in history is my teacher.” Both lessons matter. When President Vladimir Putin justified invading Ukraine by citing imperial maps, I responded with a map of the Mongol Empire and wrote: “Don’t worry. We are peaceful and free now.” That post reached twelve million people. Humor can sometimes pierce propaganda better than anger.

But the lesson is profound. Old maps tempt new tyrants. Freedom is never guaranteed; it must be defended in every generation.

Democracy survives when people remember that it is never finished. Young Mongolians today protest corruption, nepotism, and oligarchic capture. They organize, mobilize, and win victories. They prove that democracy is not a one-time achievement but a living system that must be renewed.

To preserve freedom at home, one must defend it abroad. We are no longer voiceless. Technology gives ordinary citizens megaphones that are more powerful than governments once had. The struggle for human dignity, from Ukraine to Hong Kong, Myanmar to Iran, is interconnected. Silence in one place strengthens repression everywhere.

I believe in this simple truth: resistance is possible. It was possible for herders’ daughters and sons in Mongolia in 1989. It is possible for minorities under pressure in today’s empires. It is possible for young people anywhere who refuse to accept that tyranny is destiny.

Never hopeless

Freedom does not always arrive quickly, nor does it come without setbacks. But once it touches a nation, it never disappears completely. It waits in the human heart, ready to rise again.

The world is drifting into an age of authoritarian temptation. Yet Mongolia proves that ordinary people can claim extraordinary freedom even in the most unlikely places.

Our revolution was modest, peaceful, and grass-roots. But it carried a universal message:

Democracy is fragile but it can survive next to empires. It can outlast dictatorships. It can belong to herders, workers, students, and dreamers. Above all, it can be defended by each generation willing to resist.

Resistance is always possible. Ultimately, it is freedom’s greatest weapon.

Elbegdorj Tsakhia is a distinguished visiting fellow at the Hoover Institution. A champion of human rights and democracy around the world, he served as Mongolia’s prime minister in 1998 and from 2004 to 2006, and then as president from 2009 to 2017. He is a senior mentor for the Hoover Institution’s Human Security Project, which pursues research designed to generate actionable insights into how authoritarian regimes sustain power and how those systems can be challenged to advance liberty. Learn more about President Elbegdorj as he speaks with H. R. McMaster on Battlegrounds: International Perspectives.

Liberty Amplified features the voices of those who defy autocracy in pursuit of freedom as part of the Hoover Institution’s Human Security Project (HSP). Led by Lt. Gen. (Ret.) H.R. McMaster, senior fellow at the Hoover Institution and 26th assistant to the president for National Security Affairs, (HSP) pursues research, generates actionable insights, strategies, and tools for understanding how authoritarian regimes sustain power and how pro-democracy groups and like-minded allies can challenge those systems to advance liberty. HSP serves as an educational resource and tool for activists in-country and those externally, promoting freedom and democracy.