This article is part of Liberty Amplified, a recurring series produced in partnership with the Hoover Institution’s Human Security Project, featuring voices that challenge authoritarianism in pursuit of freedom.

By Arkar Hein

On a humid evening in a small township in central Myanmar, a group of volunteer medics worked by the light of rechargeable lamps. The power grid had collapsed months ago after repeated airstrikes and sabotage. The clinic was a wooden house reinforced with sandbags. On a bamboo stretcher lay a farmer, his leg torn by shrapnel from an artillery shell that landed near his village. The medic treating him was once a government nurse in a district hospital. She had joined the Civil Disobedience Movement after the military coup in 2021 and fled to the countryside. Now she worked without salary, without reliable medicine, and often without sleep.

When asked why she stayed, the medic gave a simple answer: “If we stop, there will be nothing left for the people here.”

In December, the military had carried out a devastating nighttime airstrike on a hospital in the historic town of Mrauk-U in Western Myanmar, an area beyond junta control. The bomb collapsed wards onto patients and staff, killing more than thirty people as the building was reduced to ruins by morning.

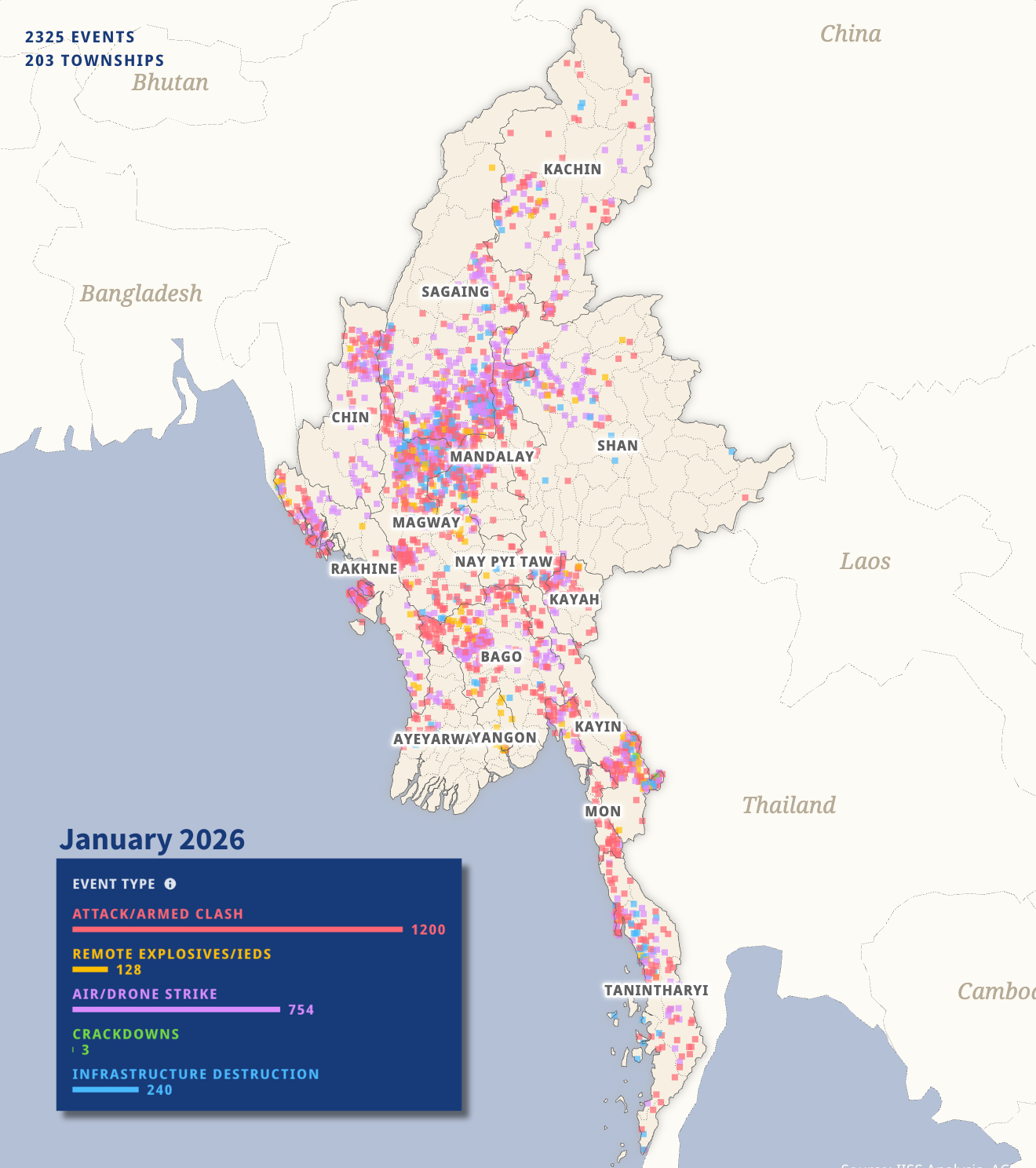

Scenes like this unfold every day across Myanmar, formerly known to English speakers as Burma. Yet beyond the country’s borders, the ongoing popular resistance against the military regime has largely slipped from global headlines. The military coup in February 2021 shattered the country’s fragile democracy, leading to an outpouring of international outrage, mass protests, and emergency meetings at the United Nations.

For a brief moment, Myanmar became a symbol of democratic resistance. But five years on, the world’s attention has shifted to other crises.

What has not shifted is the reality inside Myanmar. Across the country, communities continue to resist military rule not only with weapons but with schools, clinics, and local administrations that attempt to replace the state the military has broken.

A nationwide, people-led resistance

Myanmar’s resistance may not fit in well with the classic understanding of revolution as a single movement with a unified command. It is, in fact, a patchwork of local armed groups, ethnic organizations, civil society networks, and ordinary citizens who have taken extraordinary risks.

In the early months after the coup in February 2021, millions joined peaceful protests. When the military responded with live ammunition, mass arrests, and torture, the movement shifted its direction. Young protesters fled cities to join long-standing ethnic armed organizations along the country’s borders that have been fighting for autonomy. Civil servants walked away from their jobs in a nationwide strike known as the Civil Disobedience Movement. Teachers, doctors, engineers, and clerks abandoned stable careers to resist the junta.

In one township in Sagaing region of Central Myanmar, a former midlevel government administrator now serves as a volunteer official for a local administrative council called the People’s Administrative Team. He collects small taxes from traders and farmers not for personal gain, but to fund basic services. “Before, I worked for the state,” he said. “Now I work for the people. The risks are higher, but the purpose is clearer.”

Similar stories can be found across Myanmar’s heartland and border regions. What began as a protest movement has evolved into a decentralized, nationwide resistance. It is messy, fragmented, and often under-resourced. But it is also resilient, rooted in local communities rather than a single political center.

Self-government grows from the grass roots

Preventing the military junta from consolidating administrative control of localities has been a central objective of the country’s diverse popular resistance. Historically, successive military regimes in Myanmar have relied on local administrators and police to oppress local communities and to identify and eliminate any threats to military control. The resistance, therefore, puts a priority on grass-roots action, seeking to: 1) prevent the military junta from establishing control over local administrative structures; 2) dislodge junta-aligned local administrators and police departments; and 3) establish local administrative structures that are supportive of the resistance movement.

A degree of self-administration has been in place for decades in the major ethnic minority areas, such as Kachin, Karen, and Chin states and parts of Shan state. The center of the country, by contrast, comprising the seven Bamar-majority regions, has historically been controlled from Nay Pyi Daw by the Ministry of Home Affairs Department of General Administration (GAD), largely employing retired military personnel.

With the rise of armed rebellion in majority areas, most of the GAD structures have collapsed and are being replaced by local administration under the protection of various resistance forces. In many areas, striking civil servants from the Civil Disobedience Movement, formed in the early days of the coup, along with local civil society organizations, are now providing education, medical, security, and other community services, as well as administrative functions.

In the past four years, there has been a steady growth of self-government in more than half of Myanmar’s rural areas where resistance forces and ethnic armies have the power to keep out military junta ground troops. In these areas, the military increasingly relies on air power and artillery to try to cow the civilian population.

For their part, the anti-regime locals in some regions rely largely on tradition. While the context is new, rural communities have a long history of welfare administered by local charities, self-help associations, and religious groups and sustained by a tradition of community mutuality and barter. Recent studies of Chin, Sagaing, and Rakhine states have found that this tradition, which filled in for state negligence, has intensified markedly since the coup. It is a critical factor in sustaining the resilience of local communities and supporting resistance forces and people displaced by the junta regime. The same is undoubtedly true of other major resistance areas, such as Magway, Karenni, Kachin, and Karen states.

As the military intensified attacks on civilians and dismantled public services, entire communities were forced to improvise. In parts of the country, community clinics run by volunteer doctors and nurses now serve thousands of displaced families. Makeshift schools operate under trees or in monasteries. Village committees organize early-warning systems to alert residents of incoming airstrikes.

The results are uneven. Some areas have built relatively functional local systems. Others struggle with coordination problems, armed group rivalries, and severe shortages. But the underlying pattern is clear: across Myanmar, communities are attempting to govern themselves in the absence of a legitimate state.

The real contest for Myanmar’s future

Despite the scale of the crisis, Myanmar rarely commands sustained international attention. The conflict may have no clear frontlines, no single opposition army, and no easy diplomatic solution. It is complex, fragmented, and difficult to explain in short news segments.

But the costs of global indifference are real. Airstrikes on schools and hospitals continue, with devastating tolls of children and women. Millions remain displaced. Humanitarian access is severely restricted. And the longer the conflict drags on without meaningful international engagement, the more space the military has to entrench itself.

In December and January, the military held three rounds of tightly managed “elections” in the areas it still controls. With opposition leaders such Aung San Suu Kyi still detained—the Nobel Peace Prize recipient has been imprisoned since the 2021 coup—opposition parties banned, voting absent in resistance-controlled and conflict areas, and widespread reports of coerced voting, the outcome was largely scripted in advance.

The junta-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party, led by former generals, won a landslide victory. The military junta’s leader, Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, was widely expected to become president but the constitution bars a president from serving at the same time as commander in chief—the country’s most powerful post. That has raised questions about whether he would give up his military role, especially after he signed a law creating a new Union Consultative Council that could allow him to wield influence without formally leading the government.

Yet these nominal steps toward “civilian” rule do not reflect the political reality on the ground. The military junta’s elections may provide a veneer of legitimacy, and some external actors may be tempted to treat them as a path to stability. But the endurance of the resistance tells a different story: the country’s political future is still being contested far beyond the polling stations the military junta controls.

Myanmar’s struggle therefore carries broader implications. It is one of the clearest tests of whether a popular, decentralized resistance can outlast a brutal authoritarian regime. If the movement collapses from exhaustion and neglect, it will send a powerful message to other autocrats that mass repression still works.

If it endures, however imperfectly, it could offer a different lesson that even in the face of overwhelming force, societies can organize from the bottom up to reclaim political authority, and that this very act of self-organization is a form of democratic resistance.

The military junta’s staged elections should not obscure the reality that Myanmar’s fight for liberty and justice is still unfolding and still deserves attention.

Arkar Hein is a Myanmar dissident researcher and policy specialist focusing on local governance and federalism during the country’s ongoing conflict. He has worked with international and local partners on research and policy initiatives supporting pro-democracy actors and local administrations. His work explores how bottom-up governance structures are emerging across resistance-held areas.

Liberty Amplified features the voices of those who defy autocracy in pursuit of freedom. It is part of the Hoover Institution’s Human Security Project (HSP) led by Lt. Gen. (Ret.) H. R. McMaster, senior fellow at the Hoover Institution and former national security adviser. The project carries out research into how authoritarian regimes sustain power and how pro-democracy groups and their allies can challenge them to advance liberty. HSP is an educational resource and tool for activists both outside and within those countries.