This article is part of Liberty Amplified, a recurring series produced in partnership with the Hoover Institution’s Human Security Project, featuring voices that challenge authoritarianism in pursuit of freedom.

My dear mother, I am longing to see you, writing to you with my blood letters every day.

I was in tears as I read Lin Zhao’s writings from her solitary confinement in Shanghai, in a letter dated October 25,1967. Months later, on April 29, 1968, this Christian political prisoner of Maoist China would be executed at the age of thirty-five. Those letters, which never reached her mother, are preserved at the Hoover Institution’s Library & Archives.

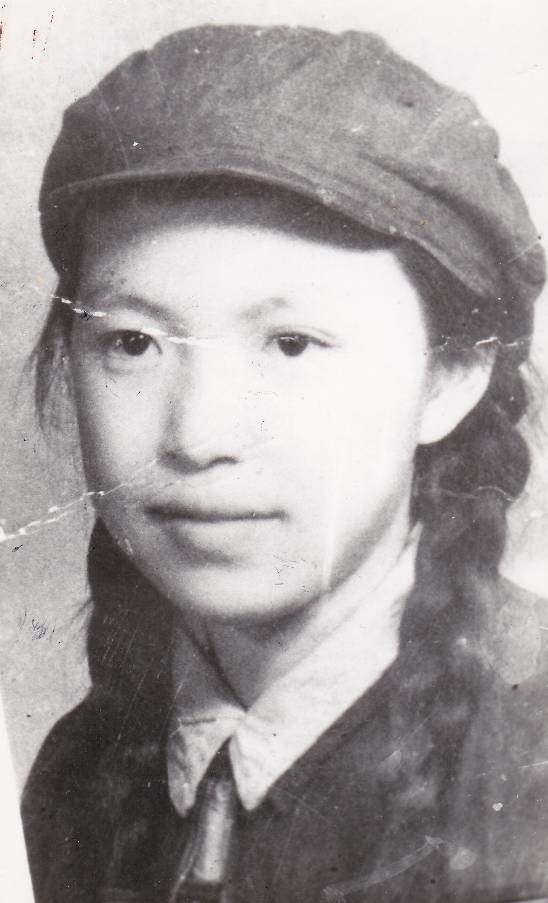

Lin Zhao, the nom de guerre of Peng Lingzhao (1932–1968), was a student of journalism at Beijing University and labeled as a “Rightist” in 1957 for her criticism of the Communist Party during the Anti-Rightist Campaign. Arrested in 1960 and rearrested in 1962, she was sentenced to twenty years in 1965 and executed three years later at the height of the Cultural Revolution.

In 2009, the Hoover Institution and Archives opened a collection of the letters and journals from her prison cell donated by her younger sister Lingfan Peng. Only a small portion of her prison writings were returned to the family after Lin Zhao was officially rehabilitated in 1981. The collection includes the official letter of rehabilitation dated December 30, 1981, labeled “criminal adjudication,” declaring Lin Zhao not guilty of all charges that led to her execution. I could tell what this document meant to Ms. Peng—even the associated envelope had been carefully preserved. She had spared no effort to clear the name of her sister.

Lin Zhao’s parents did not live to see justice for her. Her father committed suicide on November 23, 1960, exactly one month after his daughter’s initial arrest. A newspaper clipping of a Shanghai Liberation Daily editorial, titled “Historical Judgment,” also included in the collection, revealed that the authorities visited Lin Zhao’s home two days after her execution and demanded five cents: the cost of the bullet used to kill her.

When I first visited Lin Zhao’s collection at the Hoover Library & Archives in 2022, I felt I was coming to see an old friend, separated by life and death. I had just been banned from returning to my position as an associate professor of history at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, as a scholar of the 1989 Tiananmen Massacre, when the Chinese Communist Party deployed more than 200,000 soldiers, equipped with tanks and AK-47s, against unarmed civilians in Beijing.

Hand-copying Lin Zhao’s writings word by word with the pencils and papers prescribed by the archives, I was speaking to her in my mind. Now known as a “prominent dissident” and a “martyr,” she was, first of all, a human being, a woman, to me.

Mummy, I want you! Come! Please come to see me!

My dear Mummy, do you remember . . .

I want to see you! My dear Mummy, I want to see you!

Mummy, please bring me some socks—I have been wearing the same socks for three weeks.

Her outcry, a little girl for her mum, filled those pages. Sometimes she listed pages of food that she wanted her mother to bring, but which never came.

Wearing the gloves required by the archives for using primary source materials, I was touching sentences literally signed in blood: she had used it as ink to seal them with her name—Zhao—a powerful connection that sustained me in the first two years of my life in exile. I could only imagine how many cuts she had to inflict on herself to get enough blood for every punctuation of a letter more than a hundred pages long addressed to the editors of the People’s Daily, the CCP’s mouthpiece. Like many in her generation—and mine—she had been taught to believe that loyal criticism would be welcomed by the CCP and would bring positive changes to the country. But those words from this sincere Christian woman only became the evidence that led to her execution. And then in 1989 came another betrayal of loyalty, when the military crushed the dreams of democracy of a new generation.

In a journal entry titled “Mother—An Everlasting Subject,” Lin Zhao wrote:

My dear Mother! As the night is falling, I am missing you again in this solitary confinement. My dear Mother, how’s your health? It has been many months that I haven’t seen you. You must be missing me there too!

In another entry, titled “Broken Homeland Broken Home,” she wrote:

Under the rule of the Communist totalitarian tyranny, so many beautiful families have been broken! Even if people survived, they were separated! . . . (They) could not see their loved ones, leaving the world with regrets. . . . Because of me, Daddy was so determined to die . . .

As a scholar who has written a book on political exiles, in which I described the pains of not being allowed to return home to visit a beloved family member confined to her sickbed, I could not hold back my tears reading these words. In 2012, when a father committed suicide by hanging himself in an empty parking lot near Tiananmen Square, where his son had been slaughtered, I was prompted to write an op-ed in the Washington Post. I could not bear to think that this father, who gave his own life in a final appeal for justice, would die without a trace, without a record in the era of a “rising China” backed by a state-imposed amnesia.

Immediately after the Tiananmen crackdown, an elaborate “Patriotic Education Campaign” was launched through state-controlled education and media, significantly revising history and politics textbooks, selectively commemorating national glories, and recounting traumas and humiliations. History is no longer a subject matter in a classroom or a discipline of study. In 2013, an internal CCP document, known as “Document Number Nine,” listed “historical nihilism” as one of seven serious ideological problems. The term, defined as “distorting the history of our party and New China in the name of reassessment,” has become a catchphrase condemning any views of history but the official one. In 2016, China’s most influential history journal, Yanhuang Chunqiu (Annals of the Yellow Emperor), was taken over by the authorities, who accused it of “historical nihilism.”

On April 29, 2019, the anniversary of Lin Zhao’s execution, citizens in China visited her grave. An online video revealed that these people were taken directly into a police bus afterward.

The past decades have witnessed a continuing war in China of memory against forgetting. It is not merely a matter of the varying interpretations that are normal in unfettered historical inquiry. Rather, it is a state-sponsored suppression of history through punishment that has given rise to the term historicide. Individuals, specialists or concerned citizens, who refuse to go along with the official version of history are subject to punishment, risking their own erasure from the professional and public sphere.

Lin Zhao’s life story was brought to light by a 2004 documentary, In Search of Lin Zhao’s Soul, produced by Hu Jie, who quit his job to preserve her legacy. I first watched the documentary as a graduate student when it was released. Some fifteen years later, I was showing this documentary to my students in Hong Kong, during the region’s unprecedented social movement. Another documentary, Spark (2019), also produced by Hu Jie, focused on the crackdown on the college student group of which Lin Zhao was a member and eventually led to her sentence. The members of the short-lived magazine Spark had published writings critical of Mao’s policy leading to the Great Famine (1958–62), which left a death toll of 36 million to 42 million. In 2019 Hong Kong, we were still dealing with the same regime.

This month, leaders of Hong Kong Alliance, the disbanded group that organized the annual candlelight vigil to commemorate victims of the Tiananmen Massacre, were put on trial and have been accused of “inciting subversion of state power.” The government that committed the massacre is prosecuting those who commemorate it.

Recently, Hoover has added to its Lin Zhao collection, which now includes strands of her hair and a paper boat she made of candy wrappers in prison. Her voice of faith and hope from the prison cell of darkness will be heard by generations to come. The suppressed historical past is speaking to our future: the power of the powerless.

Rowena He is a research fellow at the Hoover Institution and author of Tiananmen Exiles: Voices of the Struggle for Democracy in China. A modern China historian, she is a three-time recipient of the Harvard University Certificate of Teaching Excellence. Her op-eds have appeared in the Washington Post, The Nation, the Guardian, the Globe and Mail, and the Wall Street Journal.

Liberty Amplified features the voices of those who defy autocracy in pursuit of freedom. It is part of the Hoover Institution’s Human Security Project (HSP) led by Lt. Gen. (Ret.) H. R. McMaster, senior fellow at the Hoover Institution and former national security adviser. The project carries out research into how authoritarian regimes sustain power and how pro-democracy groups and their allies can challenge them to advance liberty. HSP is an educational resource and tool for activists both outside and within those countries.